Learning to read is a fundamental part of every child’s development – but Australian kids are increasingly struggling with it.

A Grattan Institute report earlier this week found one third of students are failing to learn to read proficiently due to persistence with an older, discredited way of teaching.

The report urged schools to abandon the “whole language” method of teaching kids to read, in favour of the evidence-based “structured literacy”.

While there’s no substitute for a qualified teacher, we’ve asked the experts for their best tips for parents who want to help teach their kids to read at home, using structured literacy.

What is structured literacy?

- It’s the best-practice, evidence-based approach to teaching reading

- Structured literacy involves a combination of phonics (sounding out words) and explicit teacher-led instruction

- That’s opposed to the ‘whole language’ style, which became popular in the 1970s and has since been discredited by major inquiries across the world

- This method views learning to read as a natural process that students can master by simply being exposed to good literature

A few things before we start

First up, it’s worth pointing out structured literacy has at its core the idea that reading isn’t easy and requires two to three years of explicit teaching in the classroom.

So start by cutting yourself and your kids a bit of slack and recognise learning this foundational skill will take some time.

Whole language, meanwhile, posits that reading is easy and natural, which evidence has increasingly shown is not the case, at least not for everyone.

If your child really looks to be struggling, it’s also worth exploring whether they have a learning difficulty.

But don’t rush into chasing a diagnosis right away, according to Professor Rauno Parrila, Director of the the Australian Catholic University’s Centre for the Advancement of Literacy.

“I would first figure out what is going on in the school – is it using explicit, systematic phonics [structured literacy] instruction?”

If so, and if other interventions haven’t worked, that’s when it might be time to look at getting a proper diagnosis, he said.

Six pillars, backed by evidence

Now we’ve sorted that, what are the core principles of structured literacy and how can you put them into action?

Tess Marlen a senior policy analyst at the Australian Education Research Organisation said a good starting point is understanding the six big ideas behind the science of reading, which structured literacy is based on.

The big six came out of a landmark international study that examined 10,000 pieces of research going back to 1966 to find the practices best supported by evidence.

“Parents play an important role in supporting their child’s reading journey. The best way they can support it is to develop their understanding of the science of reading, collaborate with their child’s school and work with the school to intervene early if the child is experiencing reading difficulties,” Ms Marlen said.

Let’s break down the big six.

Phonemic awareness

This might sound like intimidating jargon, but don’t worry – the concept is just that spoken words can be broken up into different sounds.

“Phonemic awareness is when we can identify and manipulate speech sounds. It might be like isolating the first or the last sound in the word. If I said the word ‘blast’, the child can understand the first part of the word is a ‘b’ sound and the last is a ‘t’ sound,” Ms Marlen said.

You can then get more advanced and look at rhyming or alliteration.

There’s good science that children who grasp these concepts will be better spellers and readers.

Experts say to start with the basics.

“You should teach your child, for example, to recognise the letters of their own name,” Professor Parilla said.

“So you’re helping them to attach the sounds to the letters. And that’s the essential part of it.”

Phonics or ‘decoding’

This is another piece of education jargon and a word at the heart of the ‘reading wars’.

But don’t worry, it’s pretty simple too and builds on lesson one.

Students will learn there are predictable patterns that will help them “decode” the words on the page.

It often involves sounding out letters at the end of the word, such as “aw” in “saw”.

“Phonics is understanding letter-sound relationships. So that’s actually what happens when kids understand that a letter can be said in different ways. Frame has an ‘f’ sound but also cough has an ‘f’ sound but we write them differently. That’s phonics,” Ms Marlen said.

Experts suggest this can be done in a way that’s fun for your child either with magnetic letters on the fridge or silly rhymes.

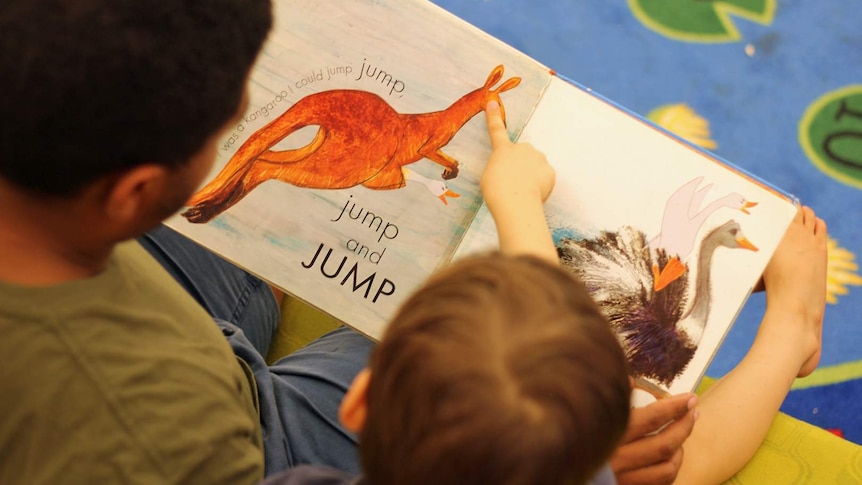

“A very good language activity is to use rhyming books for example. So have fun with the language. You use different kinds of rhymes,” Professor Parrila said.

“One of my children really loved the nonsense nursery rhymes books that didn’t make any sense, but there was a good rhythm to the language and the other one didn’t like them at all. He wanted everything to make sense.”

Other games you can play with your child at home to reinforce the concepts include an “alphabet scavenger hunt” – where you identify all the letters in the alphabet in your child’s favourite book.

If they like a sandpit you could also try “trace and say” where they trace a letter in the sand and you say it.

Another way to reinforce the lessons they get at school is to listen to your child read aloud and have them practice the sounds of words they’re struggling with.

Reading fluency

Finally, a step without jargon! This is at it sounds – the ability to read accurately and quickly.

Have your child practice reading aloud. The US National Reading Panel use this sentence as an example:

“Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see?”

Start with one word and go gradually from there. It’ll likely sound awkward and stilted ie:

“brown”

“bear brown”

“bear what”

“do”

“you see”

But the idea is that with practice, your child will be able to read aloud “effortlessly and with expression”.

This is an important skill because your child will be free to focus on the meaning of words rather than “decoding” them as above.

It will take a significant amount of practice, but the reward is that it begins to unlock the true magic of reading.

Vocabulary instruction

Woohoo! Another jargon-free concept.

Vocabulary refers to the words we need to know to communicate effectively.

Beginner readers must make sense of the words on the page by connecting them to their oral vocabulary.

Studies have shown children exposed to a larger number of words at home will do better as they progress through school.

A good way to do this is explaining the meaning of words when you’re reading your child a story.

It’s best to focus on words your child doesn’t already know the meaning of, such as “remorse”. Words like “mum” and “dad” they will have in their oral vocabulary.

“So when you’re reading books with your children, you can talk about the words in those books and then about the vocabulary. You can talk about the synonyms for those words. What other word could you also have used?” Professor Parrila said.

Text comprehension instruction

Are you still awake, class? We’re close to the end.

The idea here is simple – if students can read the words on the page but don’t understand them, are they really reading? Probably not.

When you’re practising with your child you want to see that they recognise when they understand what they’ve read and when they don’t.

Create a space where your child can ask you what a particular sentence means. For example, “I don’t get what the author means when she said, ‘arriving in Australia was a significant milestone in my grandma’s life’.”

Restate it in words they will understand, such as, “she means that coming to Australia was a really big event in her mother’s life”.

As you progress through books it can be as simple as discussing the characters you’ve just read about.

“You can ask the child about the motives, ‘why do you think she did that?’ Things like that, so the children become conscious of the thinking processes that go into reading comprehension,” Professor Parilla said.

Oral language

Ms Marlen said mastering the above five key points to reading, plus the final step, will produce confident readers.

It may be the last step but it’s another that can be started early.

“Oral language is understanding and using vocabulary to produce sentences. That develops in the early years, preschool and earlier. Children who are exposed to rich language early tend to do better,” she said.

What else do I need to know?

It’s a good idea to tell your child’s school and teacher, so what you’re doing at home complements what’s happening in class.

“It’s important to be on the ball early … following your child’s reading progress,” Professor Parrila said.

It’s also important they can put their new reading skills into practice outside of school and can see they’re valuable in real-life situations, he said.

“Provide reading materials … and work with them in in writing cards and postcards to grandma, text messages, things like that.”

If you’d like to learn more, a great place to go is the Australian Education Research Organisation.

Did you know it’s a government funded independent research organisation with a brief to conduct research and share its findings to improve children’s outcomes?

You can find lots of resources there, including Tess Marlen’s paper on the foundations of structured literacy Introduction to the science of reading.