The Arsenal Machine was at a purr. The return to the Champions League came on the heels of a five-match winning streak in which the squad returned from Dubai in top form, outscoring opponents 21-2. A three-game span saw 14 goals scored and two shots on target conceded. Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.

But the Champions League cares not about your precious league form. Arsenal flew to Estádio do Dragão and packed their carry-ons with the same general tactics that had kept things running so hot. They met a brick wall of discipline, frustration, shithousing, and ultimately — opportunism.

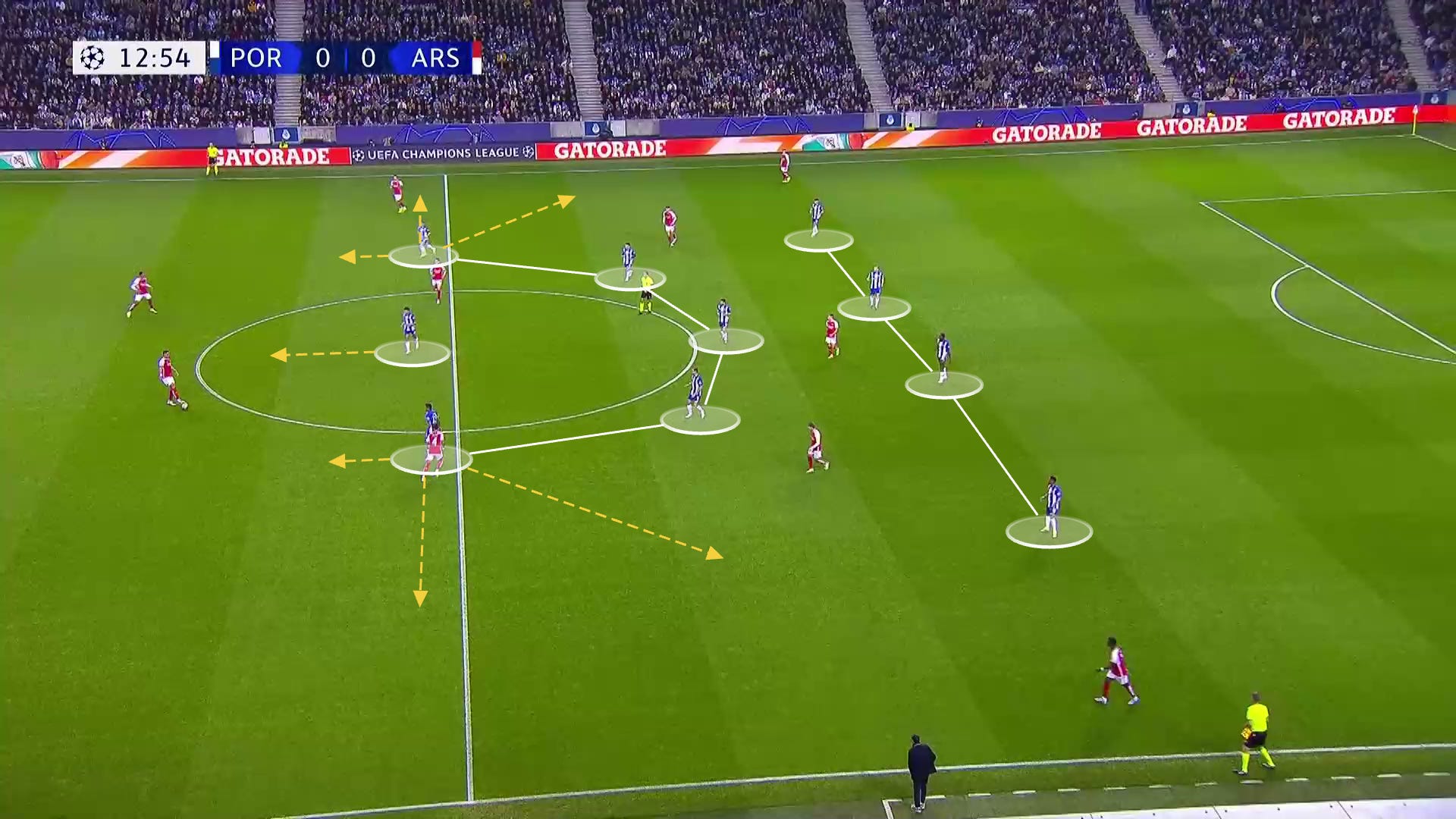

More than a familiar foe, they met a familiar tactic. Porto employed a rugged, muscular mid-block that sought to cut off all access to the middle. Porto were as compact as could be, and their wingers embraced hybrid responsibilities up and down the pitch to limit any dangerous progression. The ball was kept out of play, 36 fouls were called, and Arsenal never looked in rhythm. It was their turn to be held without a shot on target.

Here’s me talking about Porto in the preview.

In general, I would describe them as disciplined, compact, and annoying to face; they jump when you don’t want them to jump, they don’t jump when you do want them to, and they turn the game into a scrapfest with fouls aplenty. From there, they look to be decisive, relying on a lot of intuition and personal judgment in the attacking half. They have bursts of (somewhat inconsistent) attacking quality.

Arsenal are in good company. In 21/22, Fábio Vieira was on the bench for a 10-man Porto side that knocked out Ronaldo and Juventus on away goals. After our game was over, I recalled how Sérgio Conceição — the architect of Porto’s tactics — had some choice words for Pep Guardiola after a 0-0 draw in 2020.

“Were they upset? I would also be upset if I couldn’t win with the team they have and the budget they have.”

In fact, Porto just beat Benfica 5-0 yesterday! I didn’t watch, so I can’t say how mid-blocky it was.

But the point is this: smart managers use mid-blocks because mid-blocks work. This was not the first time an in-form attacking unit has met their match through this strategy. Some managers adopt it here and there. Conceição presses high in the league, but ultimately, he was born in the darkness.

The effectiveness is proven on the biggest stages.

You may recall Morocco’s brilliant run in the World Cup. In this video from the FIFA Training Centre, you’ll see the general formula: a powerful blend of total patience and total swarm that make these looks so difficult to face. Lines are created throughout the central area of the pitch to cut off all the air supply.

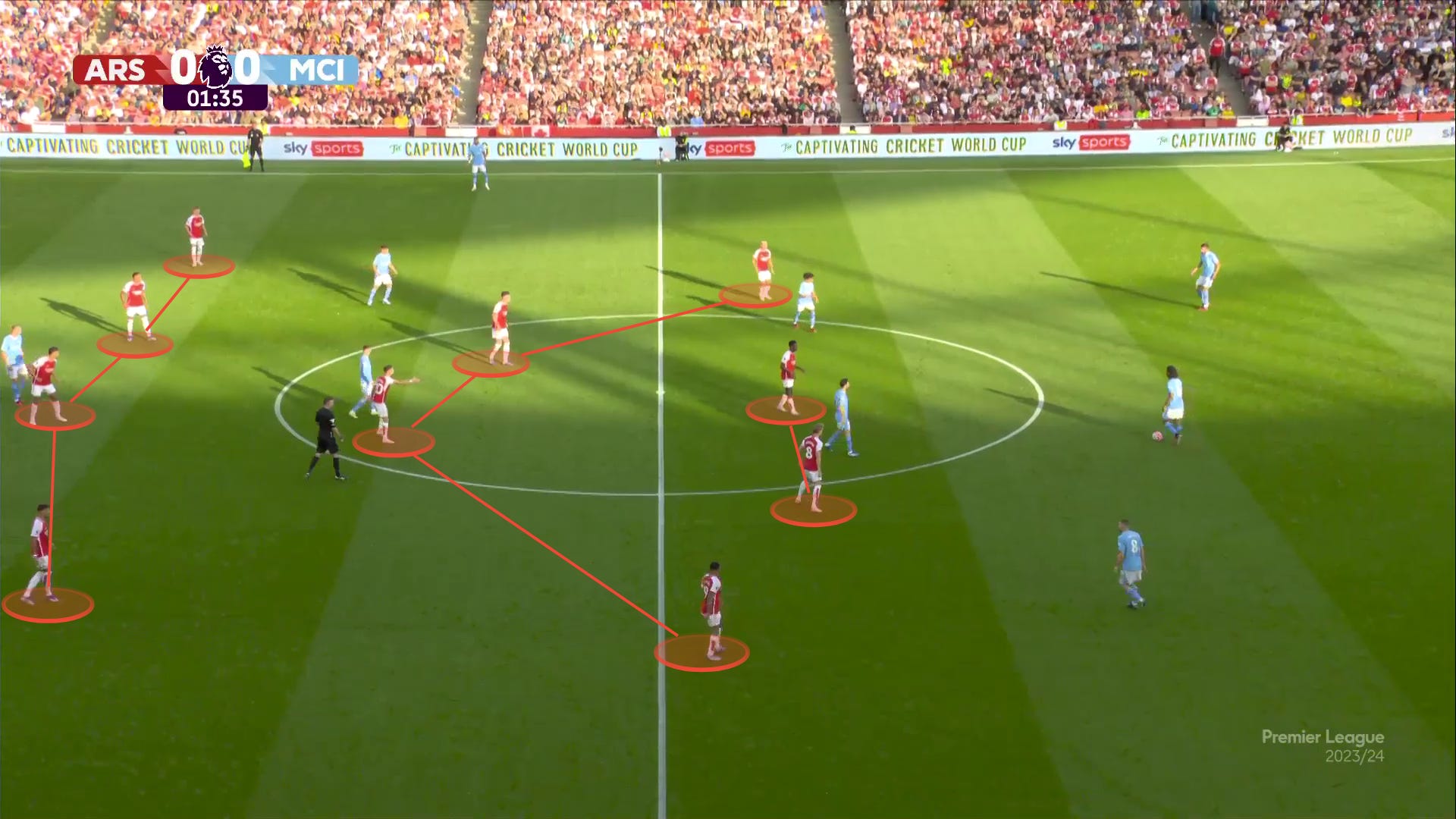

You may recall Arteta turning down the press and looking a bit like Porto for much of the match against Manchester City — to great effect.

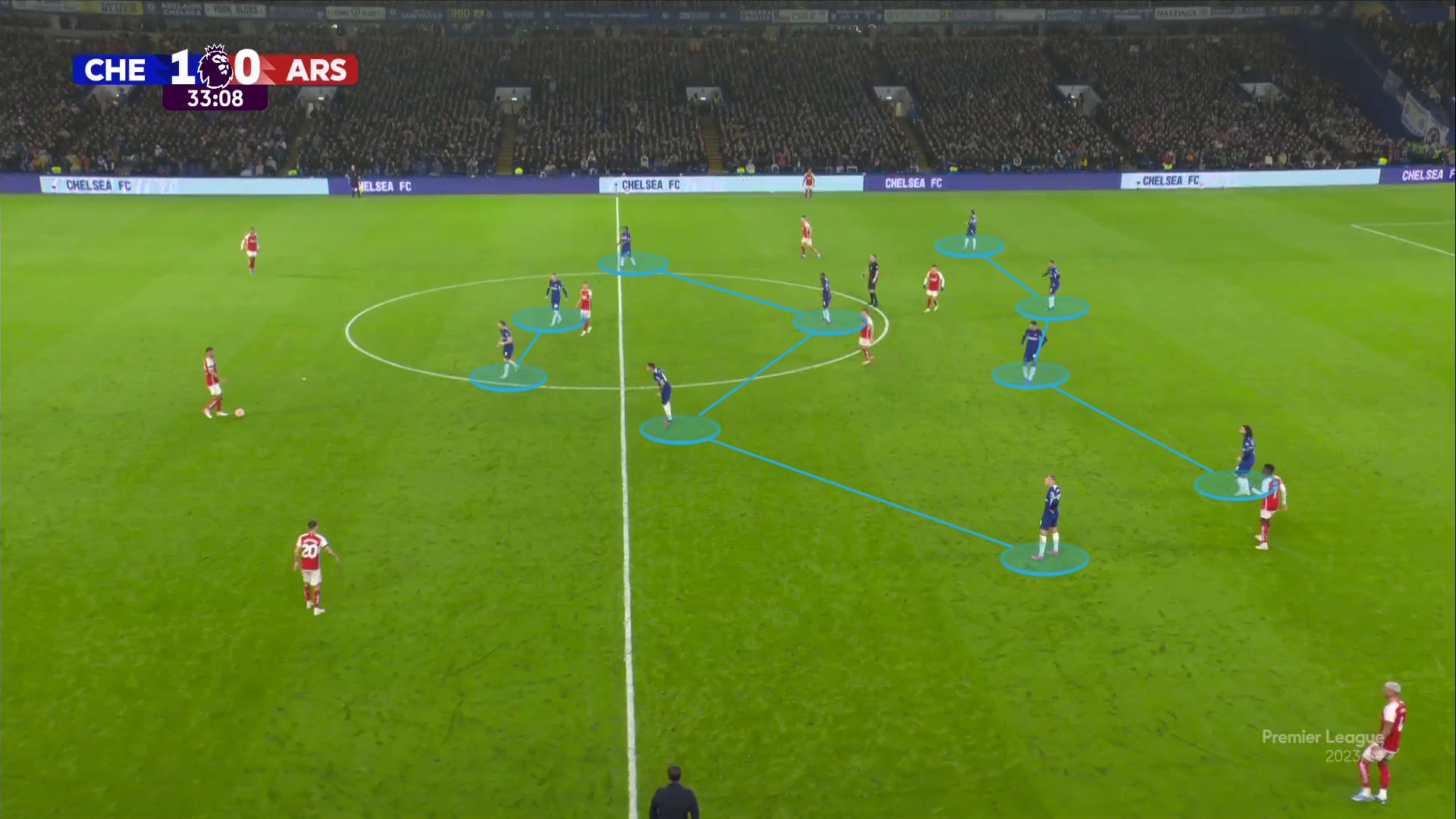

You may recall Chelsea frustrating Arsenal’s progression in a game that may have kicked off some durable changes to the team’s attacking dynamics.

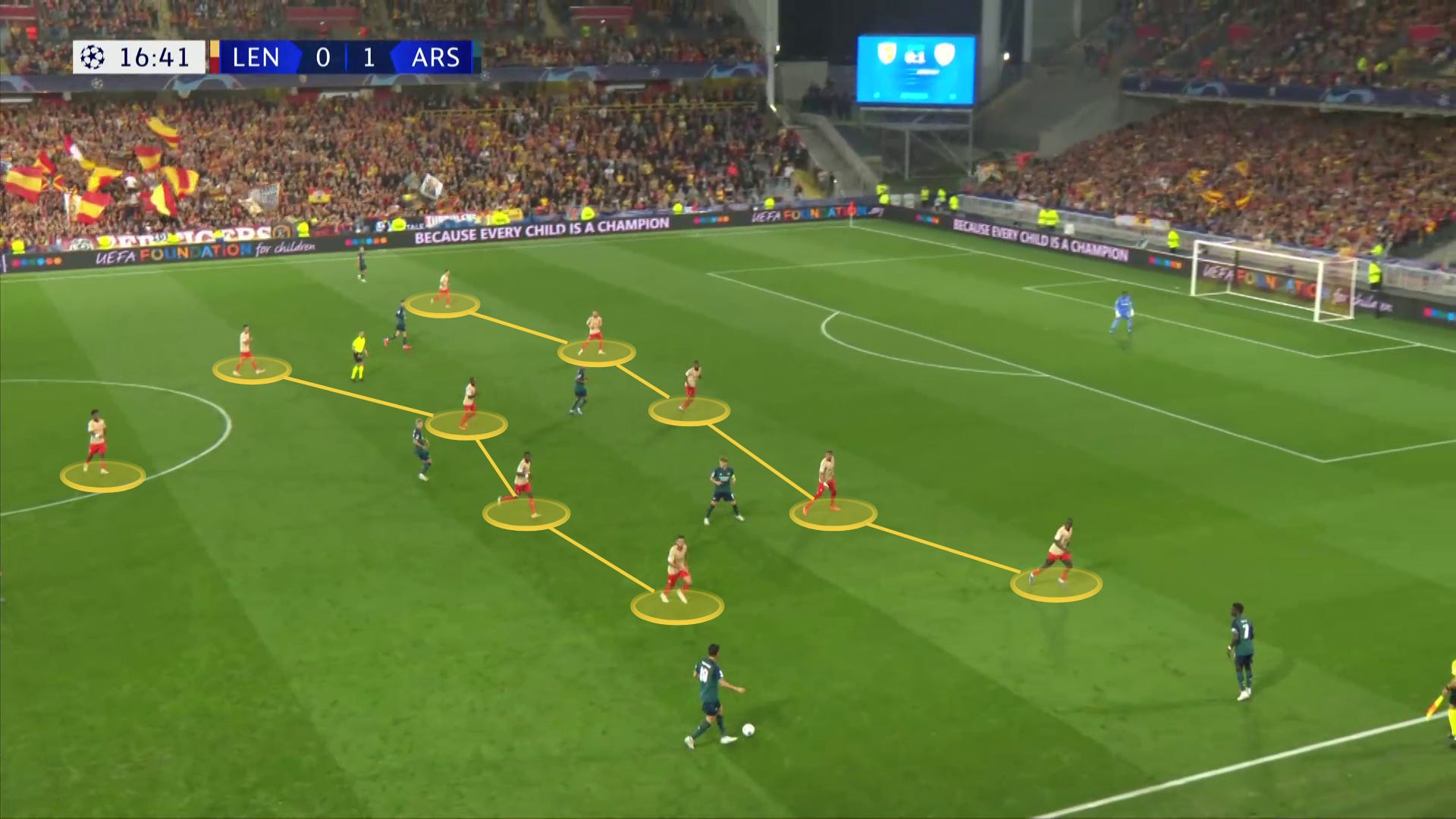

You may remember the trip to Lens, which was a vertically tight 5-4-1 look.

You may also remember four points lost to Fulham, and other frustrations.

The mid-block is a scourge!

But against Newcastle, a previous source of frustration, things got back on track.

In contrast to a cagey performance against Porto, Arsenal were shot out of a cannon against Newcastle.

Within minutes, things felt tangibly different, and the league form continued unabated in a 4-1 walloping. It might have been the team’s best performance of the year.

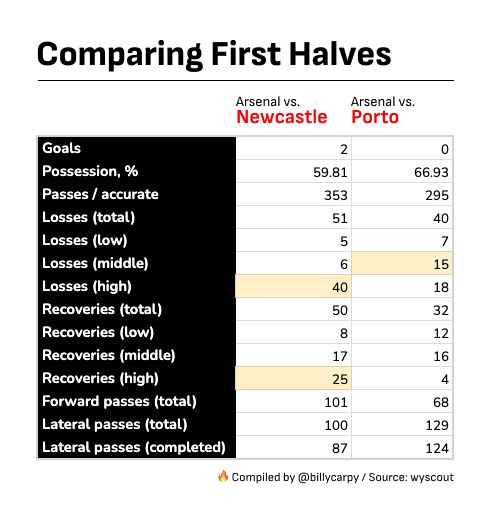

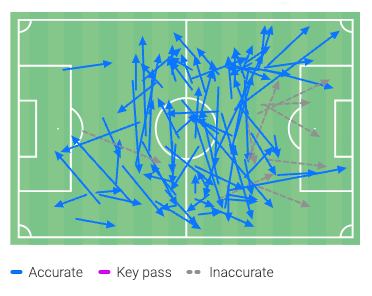

What changed? To help us understand, I pulled all the numbers from the opening stanza and included some interesting tidbits here.

Some notes:

-

Arsenal had more possession against Porto (by pure percentage), and played at a similar passing tempo, but had 58 fewer passes. This gives you a sense of how interrupted the UCL game was.

-

The other important thing to look at here is the location of the losses. Arsenal lost it 15 times in the middle against Porto, but did so a lot more in the upper third against Newcastle. Losses are not inherently bad — you’ll notice how few times Arsenal got the ball up front against Porto. Opta credited the team with zero (!) total passes into the penalty area on the night. That’s no good for obvious reasons. With riskier advanced play, you can score goals — but you can also start a “fire in their barn,” losing the ball and then winning it back as the opponent seeks to get it out of their end. Arsenal start a lot of chances this way.

-

You’ll also notice that the passing was a lot more lateral against Porto, which brings us to our next point.

Before we dive into some of the details of breaking down a block, a few obvious truths must be acknowledged.

I’d been working on this newsletter before Newcastle. In the process, I tweeted this:

I have begun researching my dissertation (aka, stupidly long newsletter) on destroying the best mid-blocks and have been watching how teams break the seal against them in even game-states. Let me tell you, it’s mostly corner kicks. Fuck.

It’s true. I kept thumbing through clips of teams scoring against mid-blocks, and it felt like the playlist that Nicolas Jover watches before bed. It can be so difficult to break through these things. Dead balls offer one of the best opportunities.

After posting that, you’ll never guess what happened against Newcastle that broke things open.

Jon Mackenzie had a great thread up about how these set piece goals can shift the underlying foundation of the game. Once the score moves out of an even state, things tend to open up a bit, and goals beget goals.

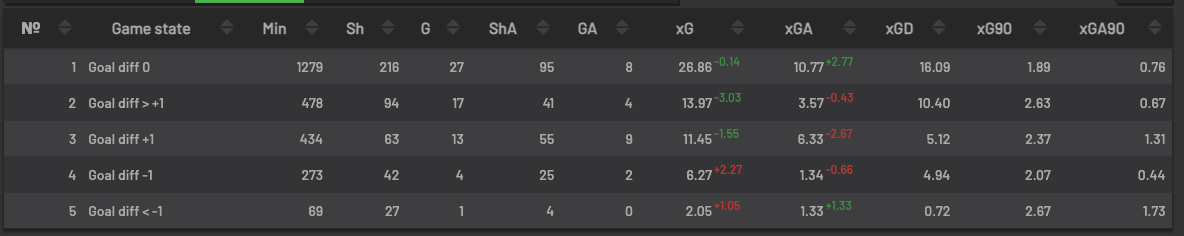

Below, you’ll see how that looks with some numbers from Understat. In an even goal differential, Arsenal generate 1.89 xG per 90. When they go up by one, that number rises to 2.37. When it’s more than one, it goes up to 2.63.

The takeaway here is to “keep scoring set piece goals.” Brilliant!

But that’s not always possible. Arsenal’s run is historically good, and Porto’s opponents are credited with zero goals via corner kick this year, and only one last year. Sometimes the opponent is stellar like Porto. Pepe and Costa are a nasty combination.

Sometimes the bounces just don’t go your way.

There must be other methods.

There is another simple, recurring truth from watching teams win against mid-blocks. The best players make the biggest difference.

If one were to over-simplify the personnel needed to win here, you need passers, occupiers, and runners. There is a specific genre of pass — those scoops or clips — that take a high degree of skill to execute with precision, but are disproportionately effective here.

So how do you break down a mid-block? Simple. You have Busquets shipping passes like this.

The rest of the clips I surveyed featured regular appearances by the likes of KDB and Alexander-Arnold placing it neatly between defenders.

Against Porto, Arsenal simply didn’t have enough of that profile on the pitch. Ødegaard has been so brilliant, but that specific kind of lifted pass is not something he unsheaths with regularity. Trossard has been sneaky-good as a runner but didn’t have the physical advantages at the 9 to be able to exploit mismatches against Porto.

Here’s what I wrote in the pre-match.

From my perspective, this is the Champions League; it’s away from home; it’s a swirling, frustrating side to play against, so cool heads must prevail; and Porto may be vulnerable on direct balls. For all that reason, I tend to pay them the respect they deserve, and go with the look we saw against Liverpool: a Jorginho/Rice double-pivot with Kiwior left-back and Havertz up top. The big game lineup.

We’ll talk tactics, tactics, blah blah blah, but that’s probably the biggest difference in the performance against Newcastle. Jorginho played. He may not be up to playing twice a week at present, so this is not necessarily a critique. Managers have all kinds of practical considerations to make that we scribes can conveniently ignore.

Jorginho was a man possessed against Newcastle, attempting 102 passes in all, with so many of them featuring the exact right amount of touch, weight, and anticipation. (I hope Zubimendi is scribbling notes.) Jorginho has been low-key direct for much of the year and wound up creating a lot of chances by himself.

But the personnel on the other side matters as well.

Newcastle have been headed in the opposite direction of Arsenal since the start of January, leaking 2.86 goals per game in 2024. While injuries tell part of the story, a lot of it has stemmed from a difficulty modulating away from their highest-intensity style.

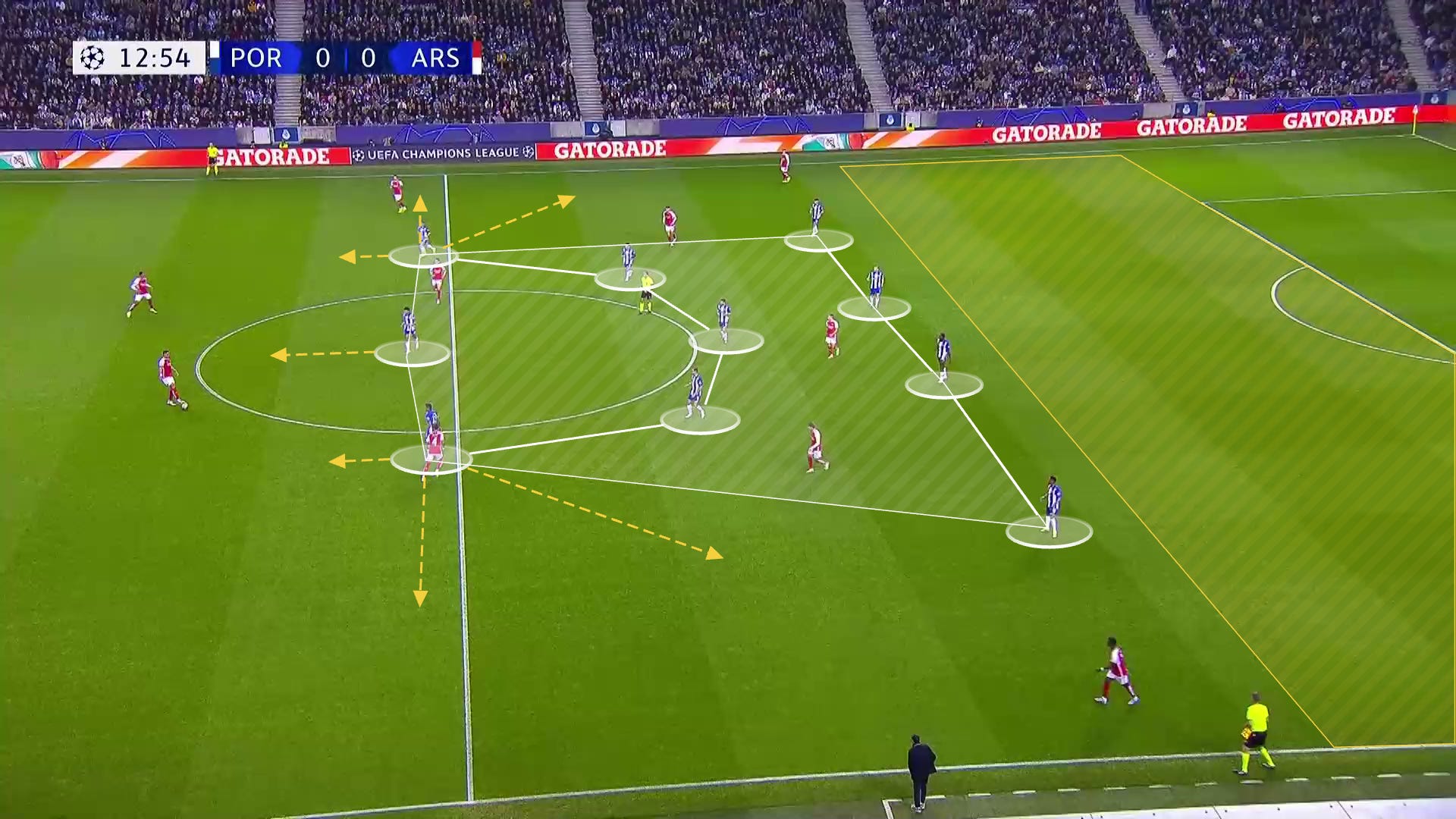

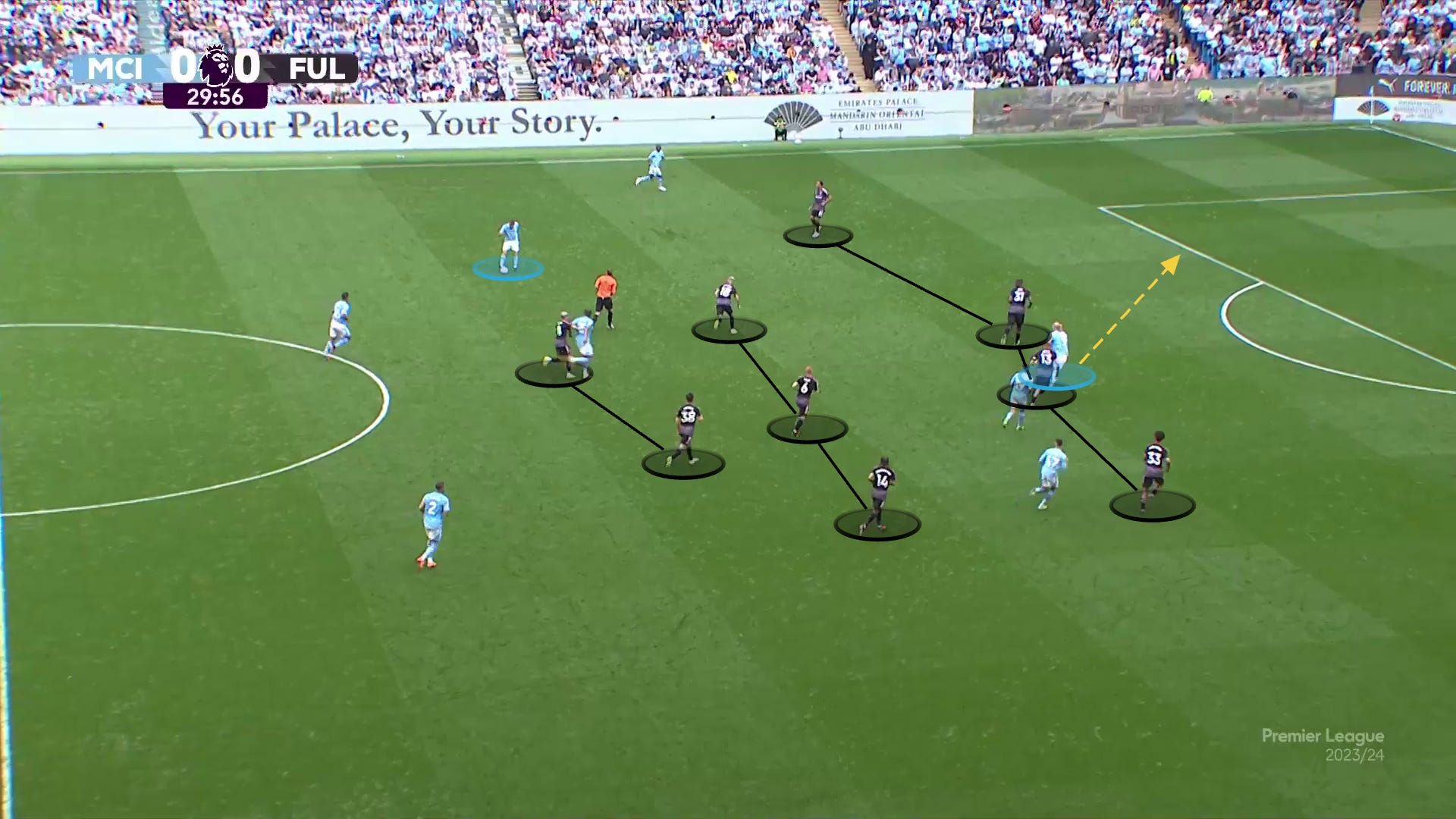

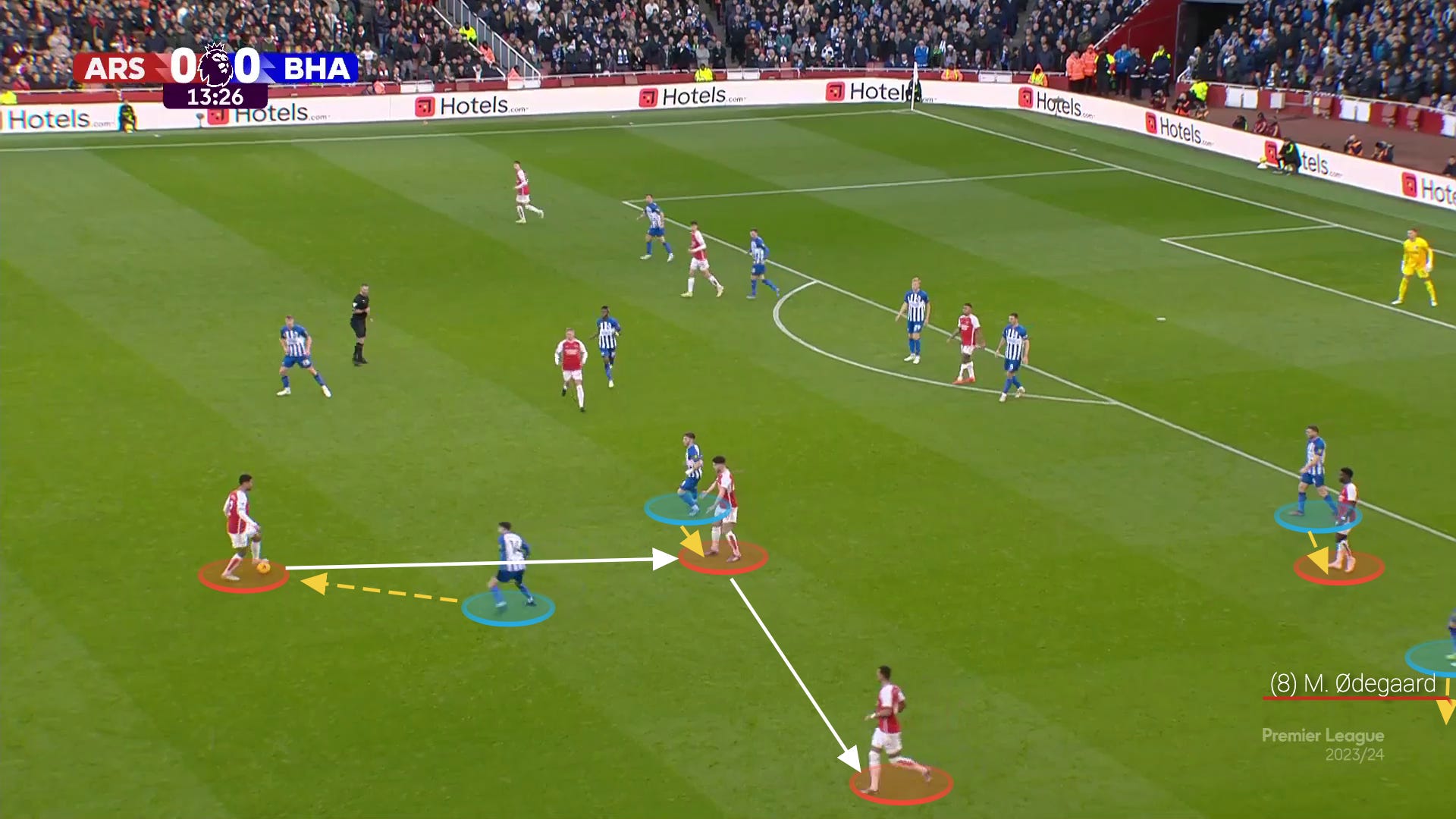

Against Arsenal, there were many of the same root tactics we saw in Porto. The problem? The distances and energy weren’t maintained with the same level of absurd stubbornness. In particular, this gap (in yellow) was often open — the shadow-marking by that midfielder and the winger weren’t up to snuff. The same door was closed in Portugal.

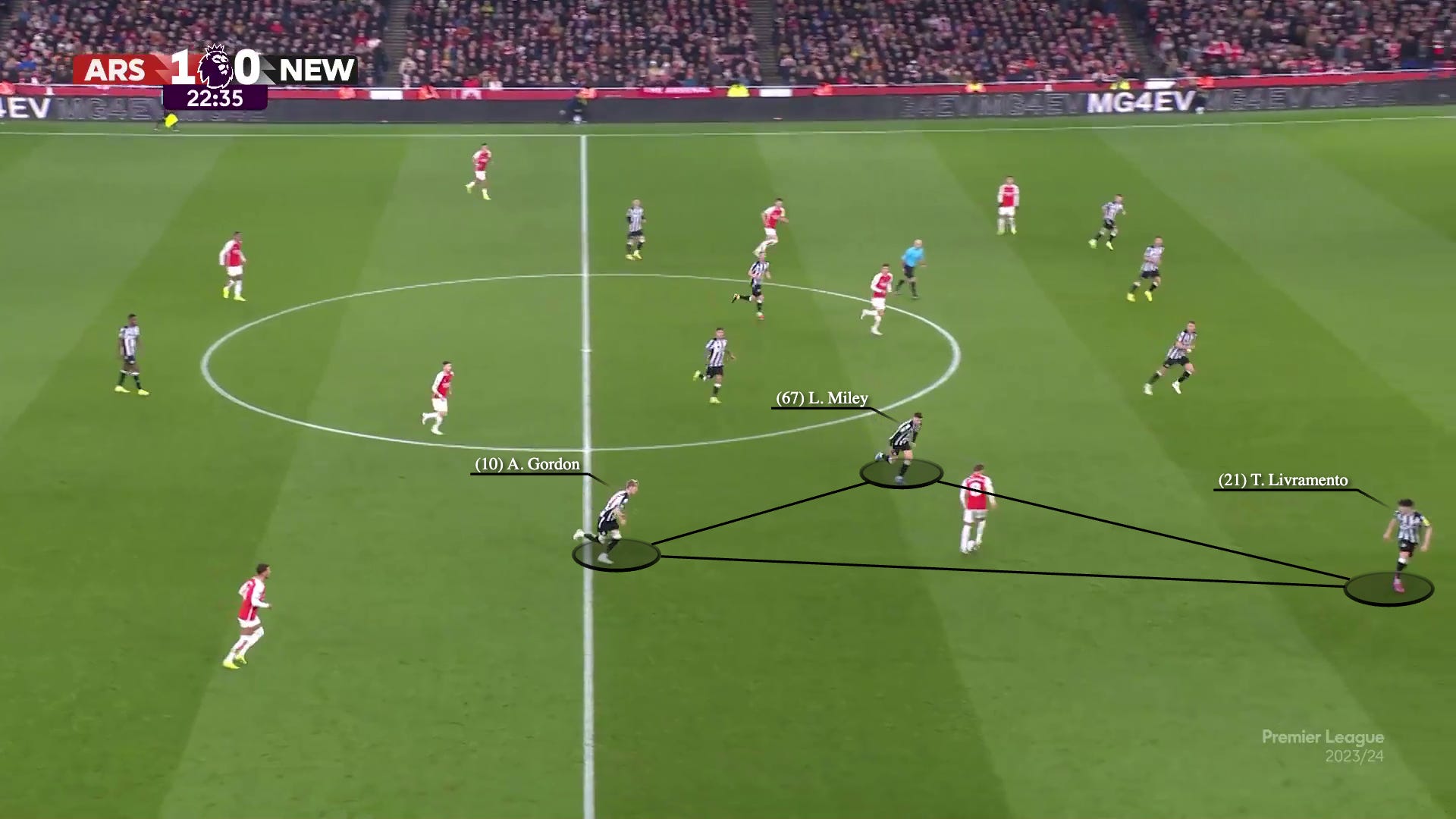

And you’ll see how quickly it can turn and flip into an attack. This triangle — Livramento, Gordon, Miley — are uber-talents. But they also have an average age of 20.33, and were too easily moved around by the more experienced Arsenal players.

The players matter.

But however dominant and swashbuckling Arsenal looked against Newcastle’s midish-block, laurels shouldn’t be rested upon. Just a couple of weeks ago, we wrote Block Buster, a long exploration of the system used to destroy West Ham. But the piece itself was oddly measured, and mostly dedicated to “devil’s advocate” concerns with that setup, despite the 6-0 scoreline. Some issues were simmering there, but — repeat after me — a couple of set piece goals poured in, and it was wide open from there.

A sense of healthy paranoia should be maintained, lest there be a repeat of Fulham or Porto when it really matters.

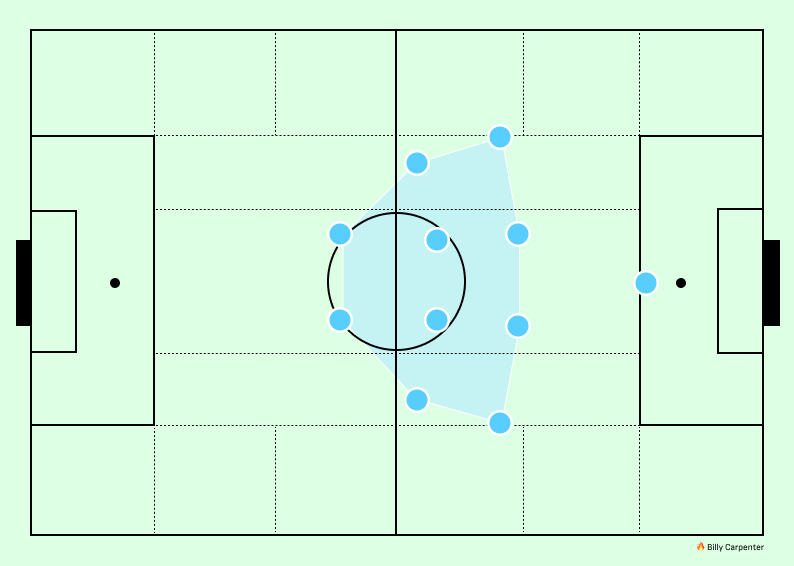

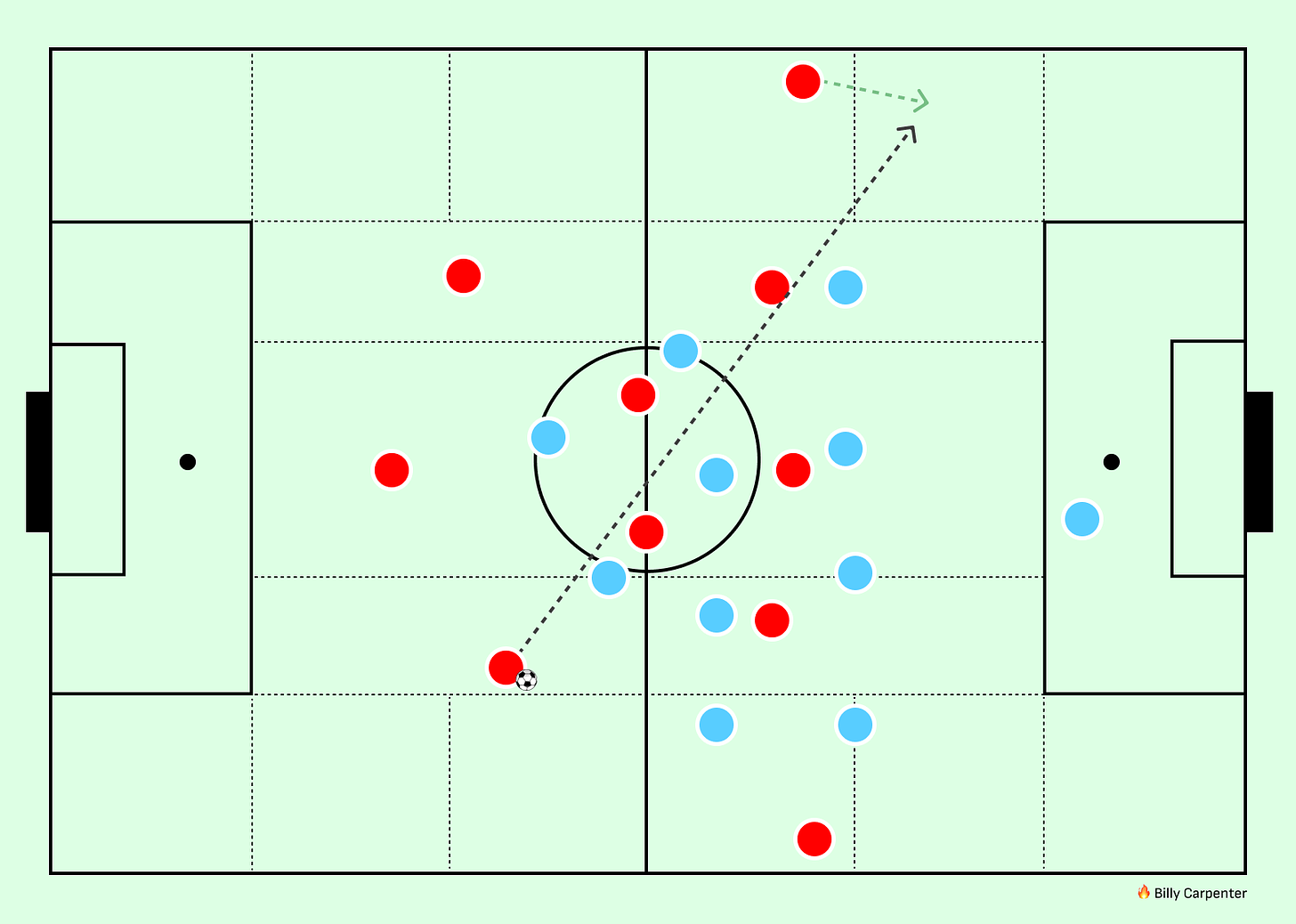

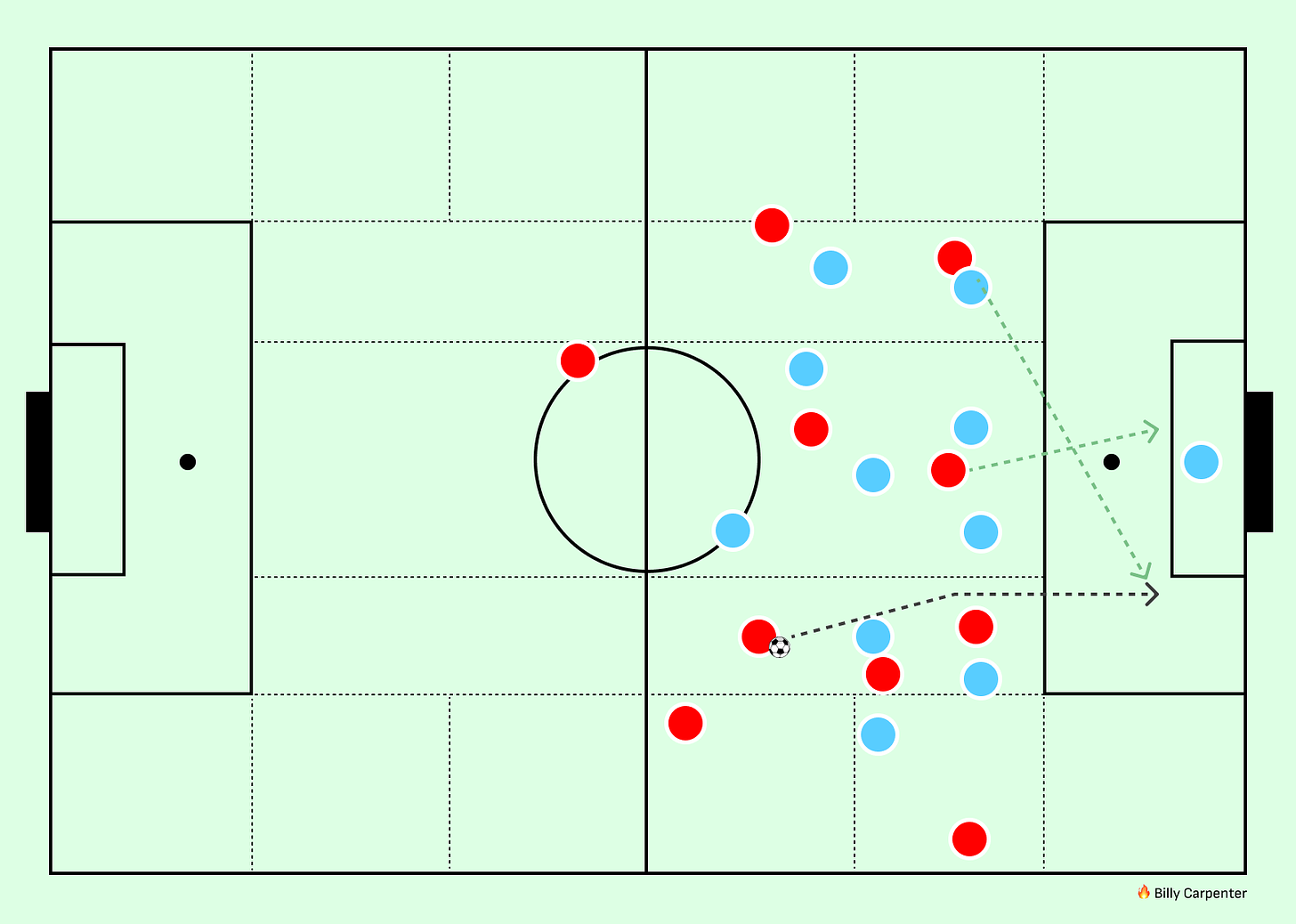

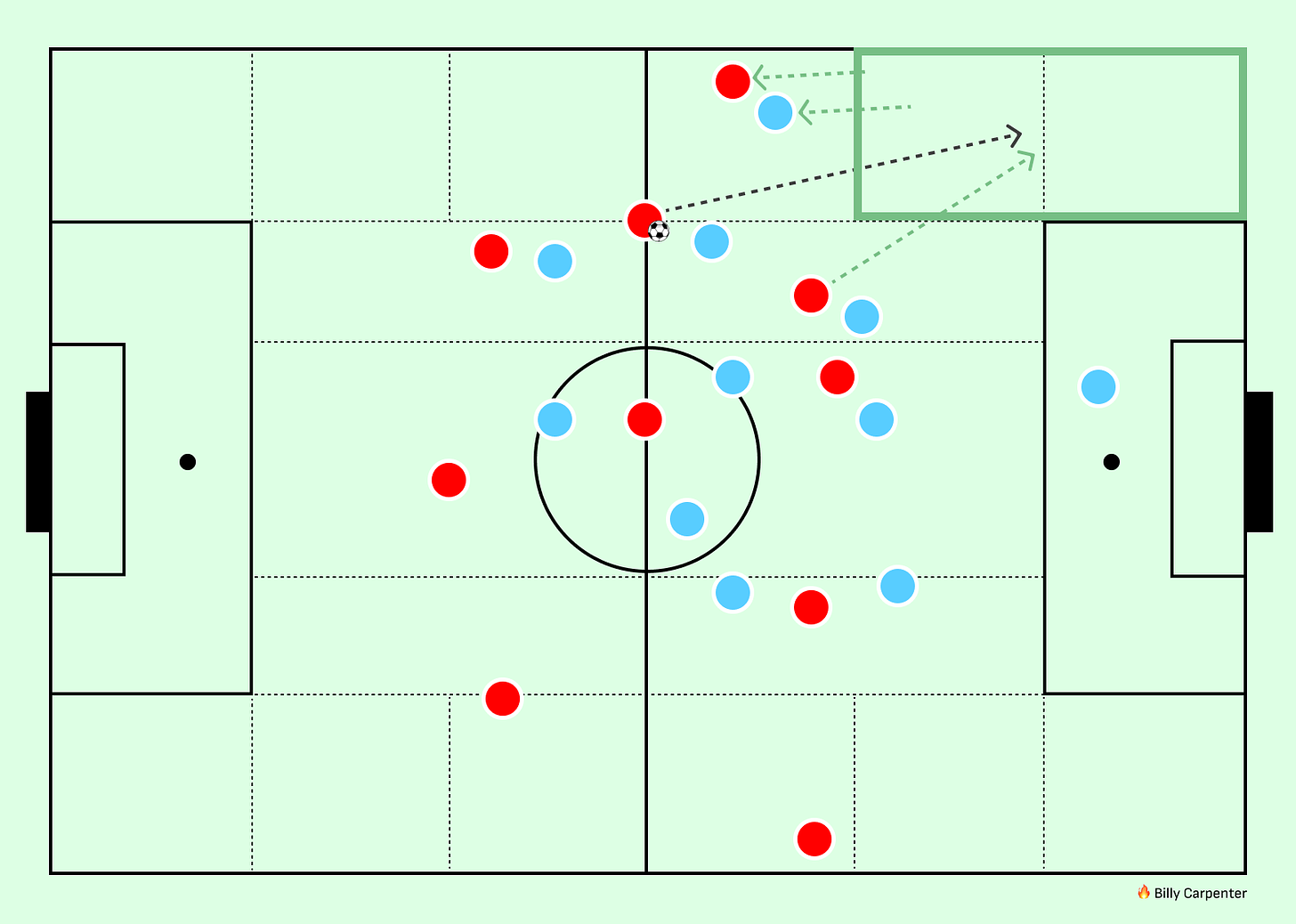

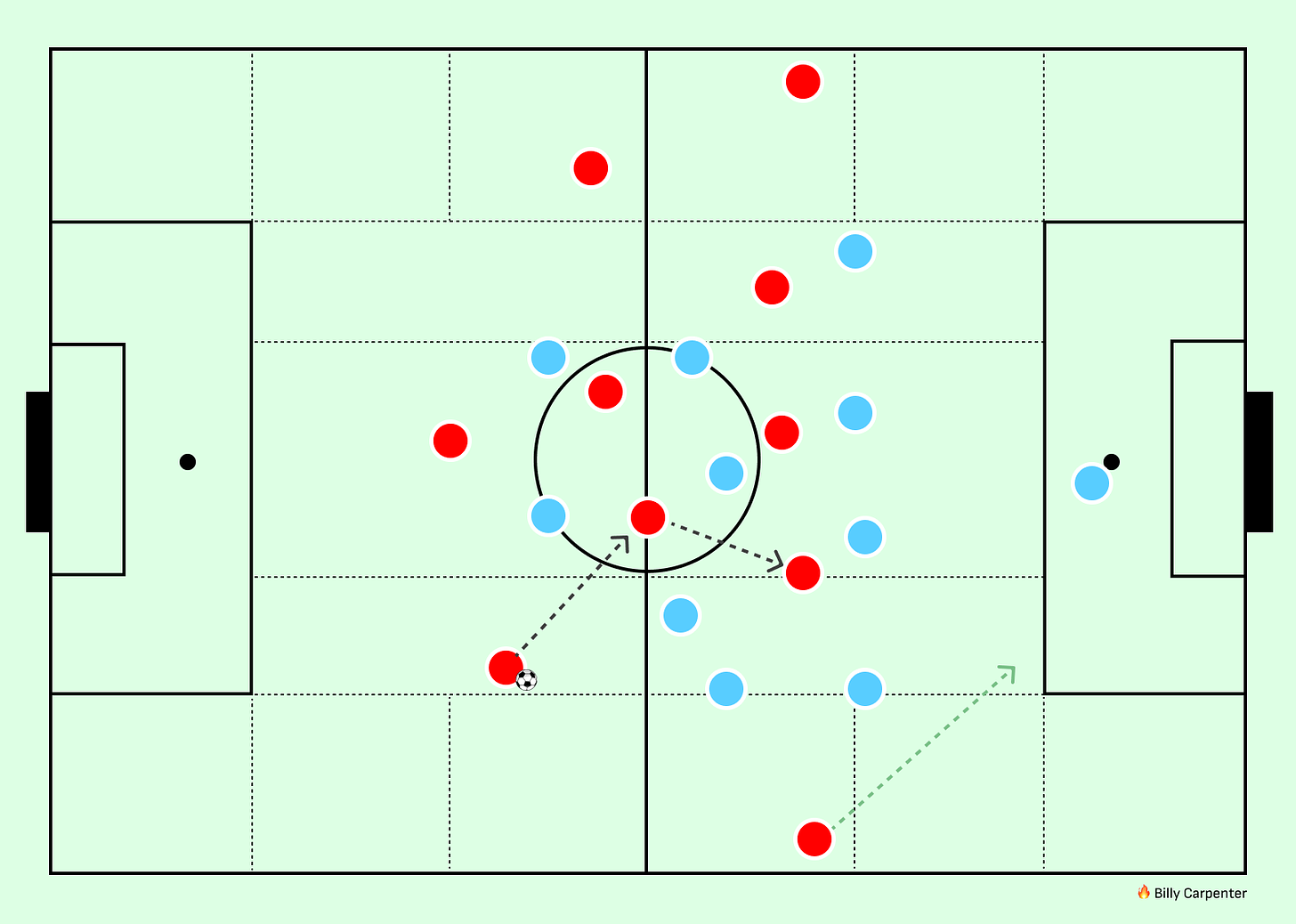

I drew up a new tactics board to help illustrate my points today. How does this look?

What you’ll see above is a typical 4-4-2 mid-block. The numbers don’t really matter that much in out-of-possession set-ups, as every player tends to have a specific set of instructions — but it is nonetheless a helpful shortcut. Teams use anything from a 5-3-2 to a 4-5-1. Some of these set-ups even have six players in the back.

A mid-block is predicated on a few factors.

-

Condensing the pitch: Football is a unique sport in that teams can make proactive decisions about where they want to engage and how big the functional playing area is. A mid-block seeks to keep the game in an advantageous, winnable area for the out-of-possession side.

-

Maintaining distances: The players must work in a unit to stay close together, which blocks the opponent’s opportunity to cut lines. Players are usually between 10m-20m apart; in a compact block, that usually means that they try to keep to an area of about 40m wide and 25m tall, and maybe 35m from the backline.

-

Blocking central access: Like in chess, you have the most options as an attacker when you are in the middle of the pitch. The idea of a condensed mid-block is to take that away.

-

Jumping in winnable situations: Teams have different “lines of engagement” and “press triggers” for different matchups.

-

The line of engagement is how far up the pitch a team is willing to engage with the player with the ball; Porto will play higher against other teams than Arsenal, for example.

-

The trigger may be a ball near the touchline, a loose touch, a certain player receiving it in a certain way, a central pass, a backward movement, or any number of things. Teams are often most aggressive when a) a ball is played into the middle and the press can swarm, and b) they can use the touchline as a giant defender to squeeze a wide player (usually a wide full-back or winger). These “triggers” are usually decided in the gameplan and can run the gamut from relatively relaxed to all-out aggressive.

-

-

Keeping high-line integrity: When a back-line moves in unison, it becomes dreadfully difficult for a team to play it into the space between the last line and the goal-keeper, not get it picked up, and keep it onside. The backline moves around based on the placement of the ball and the actions of the higher units.

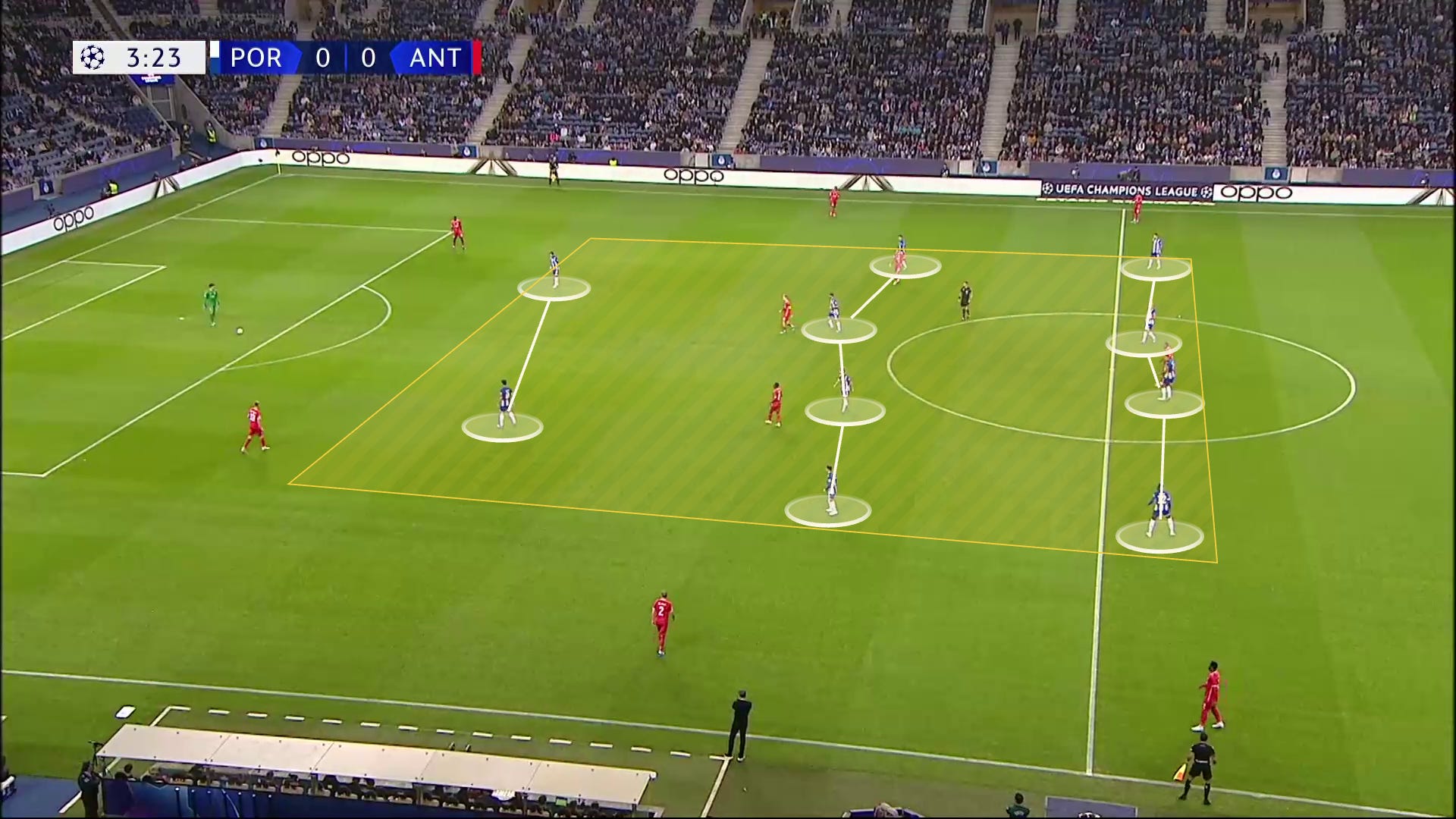

Here’s an example of Porto working with a slightly higher line of engagement against a weaker opponent in Antwerp. Most of the objectives remain the same.

And here’s a more wide-ranging look, from another FIFA training video. You can see how the team coordinates en masse. Everything is about drawing imaginary lines that cut through the middle of the pitch, and “triggering” on certain conditions — namely, the ball going in wide areas. The ball is eventually won when a less-than-advantageous long ball is played over the top.

As important as the tactical footprint is, the most important part is psychological. The team must operate with a “shared brain,” believing that their patience will pay off, their jumps will be backed up, and the shape will regroup whenever it gets momentarily stretched.

Here are a few.

-

Restrict central access — By flowing play into less threatening areas, you impact the opponent’s ability to threaten.

-

Win the ball on triggers — Compact defending means that if a ball is won, teammates can flutter out and makeable passes should be in the offing.

-

Conserve energy — This allows the out-of-possession side to maintain stamina throughout which, among other things, helps on the counter.

-

Remove baiting from build-up — Teams are getting increasingly stellar at build-up. Specifically, they’re good at baiting pressers forward and then passing through them, discarding the higher players. This is the entire foundation of Roberto De Zerbi’s tactics at Brighton. By playing in a mid-block and simply not engaging when a deep CB or GK is passing the ball, a big potential advantage is removed from the attacking side.

-

Erase the press-to-block transition phase — Most teams have a harried transitional period between when they’re pressing up high and when they move into their lower block. This removes that spot of vulnerability. You’re just always in the block.

Beating a mid-block is hard. Thanks, Billy.

But it still must be done. There are a couple of methods that seem to work quite well: scoring via set pieces, and catching the team out of shape. On the second charge, pressing is the best playmaker, and Arsenal’s press was absolutely dominant against Newcastle. But that won’t necessarily teach us a lot about beating the block itself.

So how can we find out more? I pulled a list of some of the better mid-block teams in the world. Think Morocco, Porto, Atleti, Roma, Atalanta, Fulham, Valencia, Real Betis, Juventus, Reims, and some others. You’ll suggest that I missed somebody. That’s fine. These teams have different variations — sometimes dramatically different — and there is no perfect, one-size-fits-all definition of how to do a mid-block “right.”

From there, I segmented the goals they’ve conceded in the last two years, and narrowed it down with a couple of factors to try and focus in on the times when the block was at its toughest.

How do you break the seal?

TL;DR: I pulled a playlist of ~100 goals that “mid-block” teams conceded in the first half, in open play, with an even scoreline.

I didn’t really run a statistical analysis here. I just kept a running list of notes and sought to identify some patterns. Here’s what was observed.

We’ll start with the more obvious ones.

Mid-blocks want to stay compact. What that means is that if you play it off to one side, they’ll want to keep distances short — which means they’ll lean that way together, and the other side is usually free. The trick is blasting it over to the other side with speed and skill, then attacking before they can regroup.

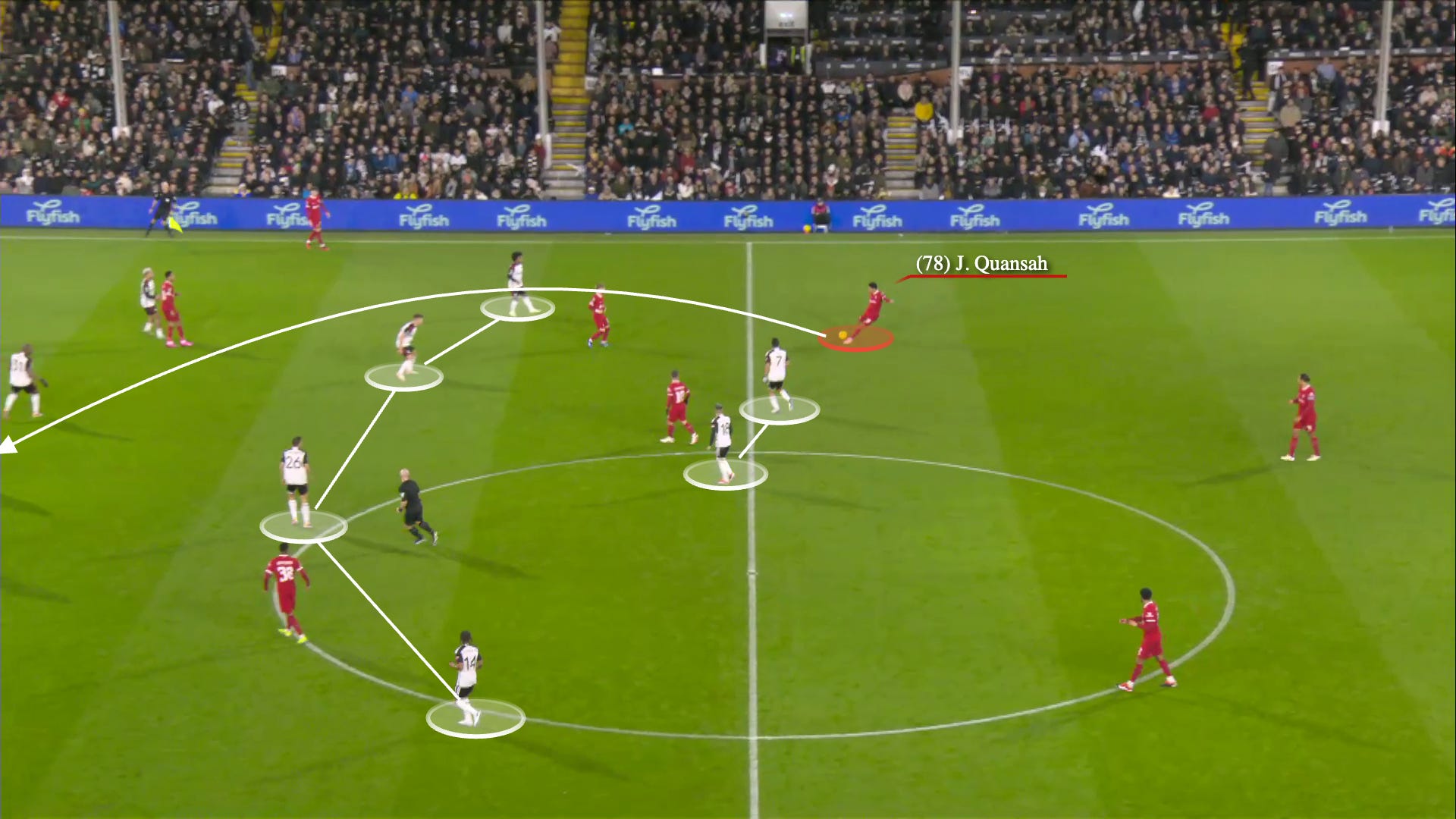

Here, you’ll see Quansah carry up to a pocket on the fringes of the Fulham mid-block. Three Liverpool attackers are in a triangle on his side, which naturally causes the Fulham shape to teeter that way. He switches it out to Luis Díaz on the other side.

Now, instead of the claustrophobia of the middle of the pitch, Díaz has a single duel to win. He does it, and as the shape desperately (and chaotically) tries to regroup, he attacks with purpose, and slots it in.

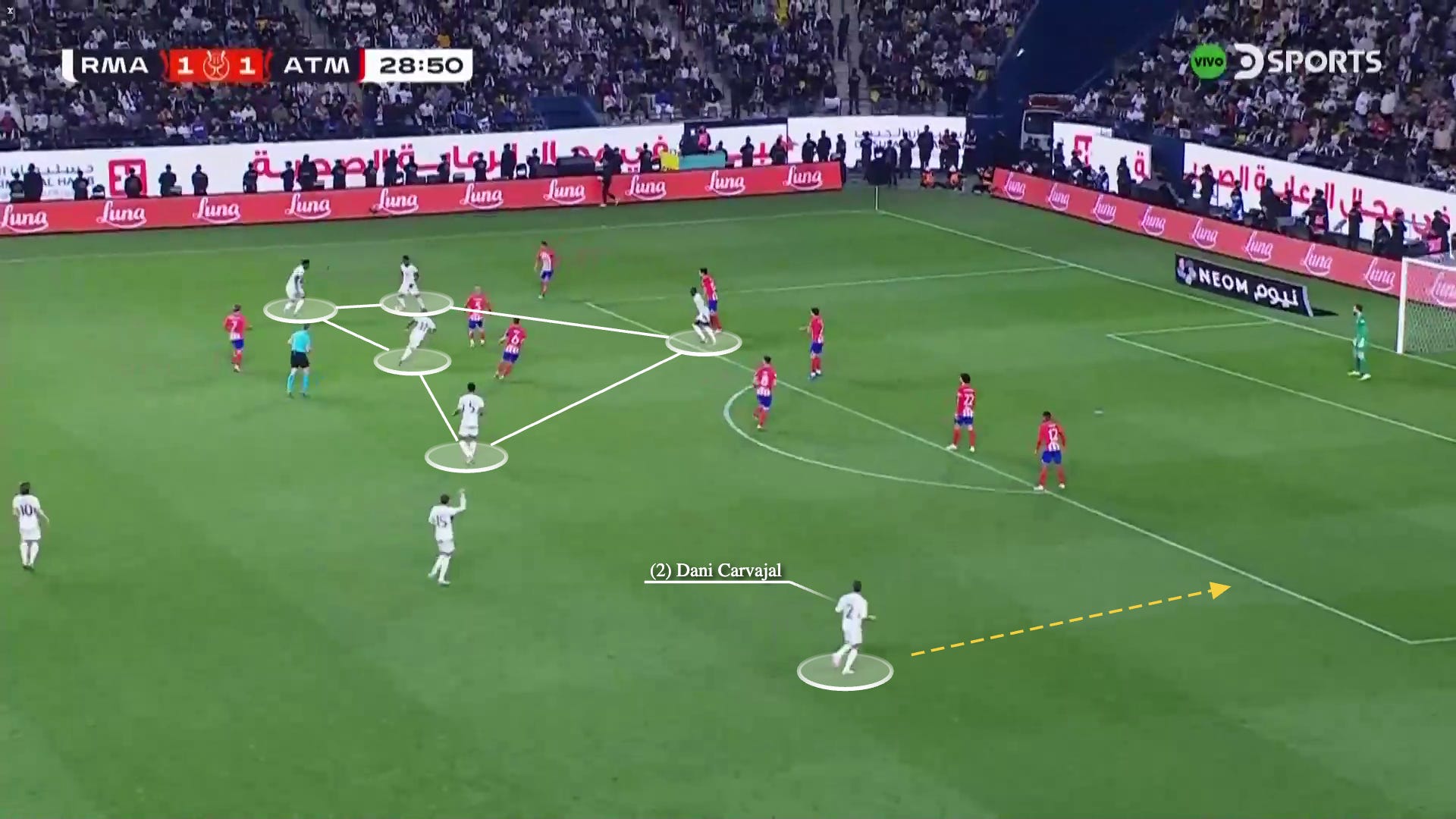

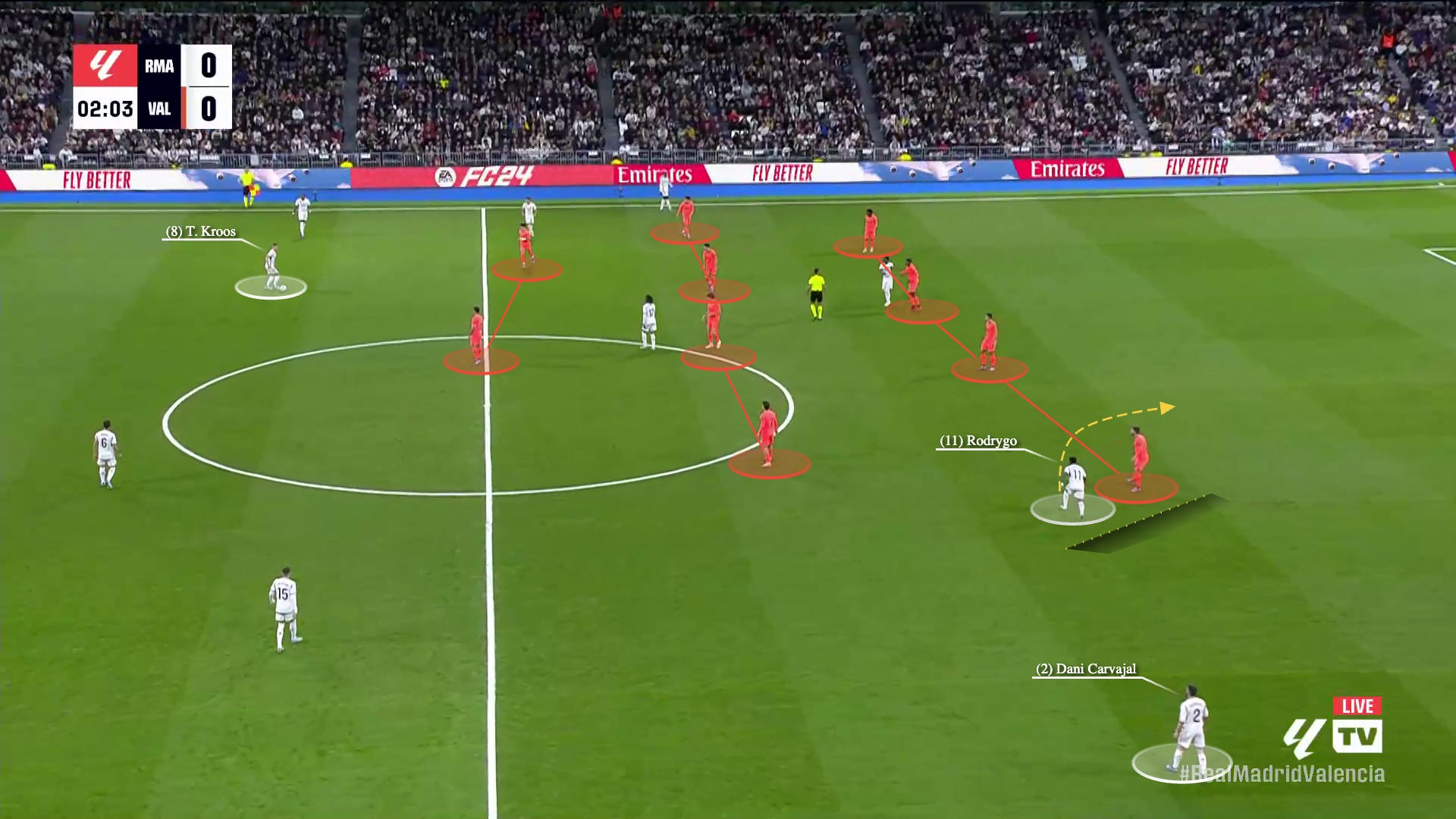

Real Madrid are great at this. They’ll build freewheeling, “relationist” shapes, with the world’s best players simply using great intuition to pass it around and create advantages. This naturally attracts a situation where the Atleti players look to disrupt their rondos. Carvajal, on the other side, is keeping width.

Now, it’s switched over to his side with speed — and the original ballcarrier (Mendy) floods the middle with haste. Goal.

This next one shows how important it is to maintain width for the attacking team. The mid-blocking team is hesitant to meet width with width, because if the backline is stretched too wide, gaps in the middle open and the team is toast.

I mentioned that much of the task of beating mid-blocks is deceptively simple, if difficult: have great passers and runners.

Well, here’s Toni Kroos.

What you’ll notice there as well is the interlocking run made by Rodrygo. By him cutting inside, the defensive full-back has to pinch as well, giving the wide player more space to operate. Timing those movements is an example of how the training ground comes to the pitch.

And there’s Caravajal again, who just needs a couple of touches while the team is out of shape before slotting it home.

And here’s a simpler, more exploitative example of this by Lino (with way weaker line integrity from the opponent).

“Duh,” I hear you say.

There is a key, structural “vulnerability” in teams that employ a mid-to-high block. I put that in air-quotes (and by that I mean … real quotes) because it is fully intentional and deceptively hard to exploit. It’s the yellow area here.

In the words of the great Admiral:

Back-lines are awfully fast these days, keepers play so high, and the eventual space — the one that is actually greeted by the squeezing defenders — is always smaller than it seems. For years, Liverpool have baited passes into this area because they’re confident they can just calmly scoop it up.

This was after the game was already cooked, but it gives you a sense of a highly-likely outcome of these balls.

So how do you beat this?

I think a way that teams falter here is by having too simple of an idea. A striker will line up directly on a CB and try to run it in behind, or a winger will get on the shoulder of a FB and try to do the same. There isn’t enough to keep the backline or GK genuinely off-balance.

It is also, as always, about passing. Arsenal saw the difference in having a player like Jorginho on the pitch.

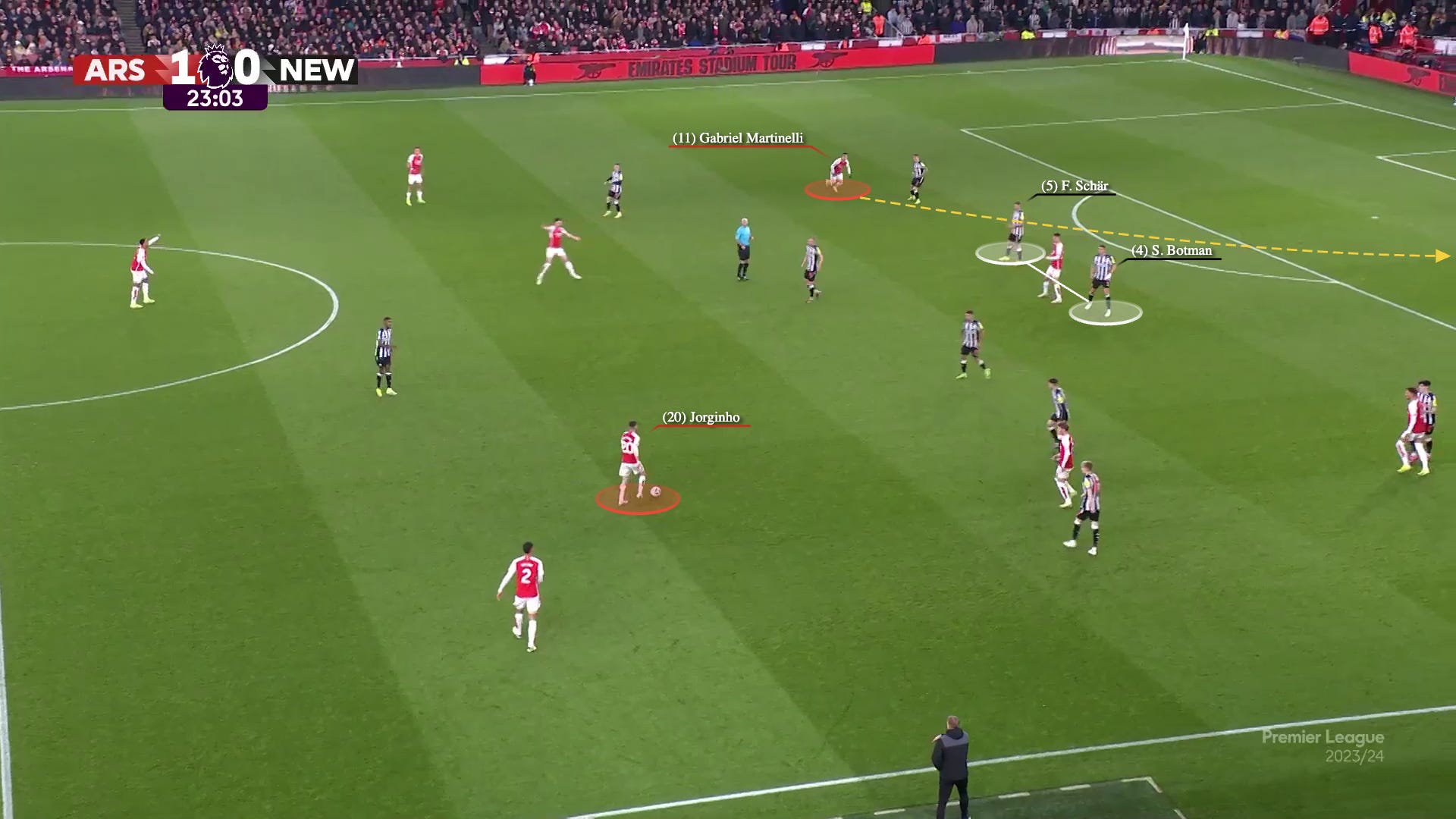

Here, we’ll start with the “before” state. Arsenal have regrouped after a ball-win, and Jorginho has received the ball without pressure (a mistake by Newcastle, imo). In this moment, you’ll see how compact the Newcastle CB pairing is. But Martinelli starts darting across zones — and this is the difference between “occupying” (what Havertz is doing) and “arriving” (what Martinelli is doing).

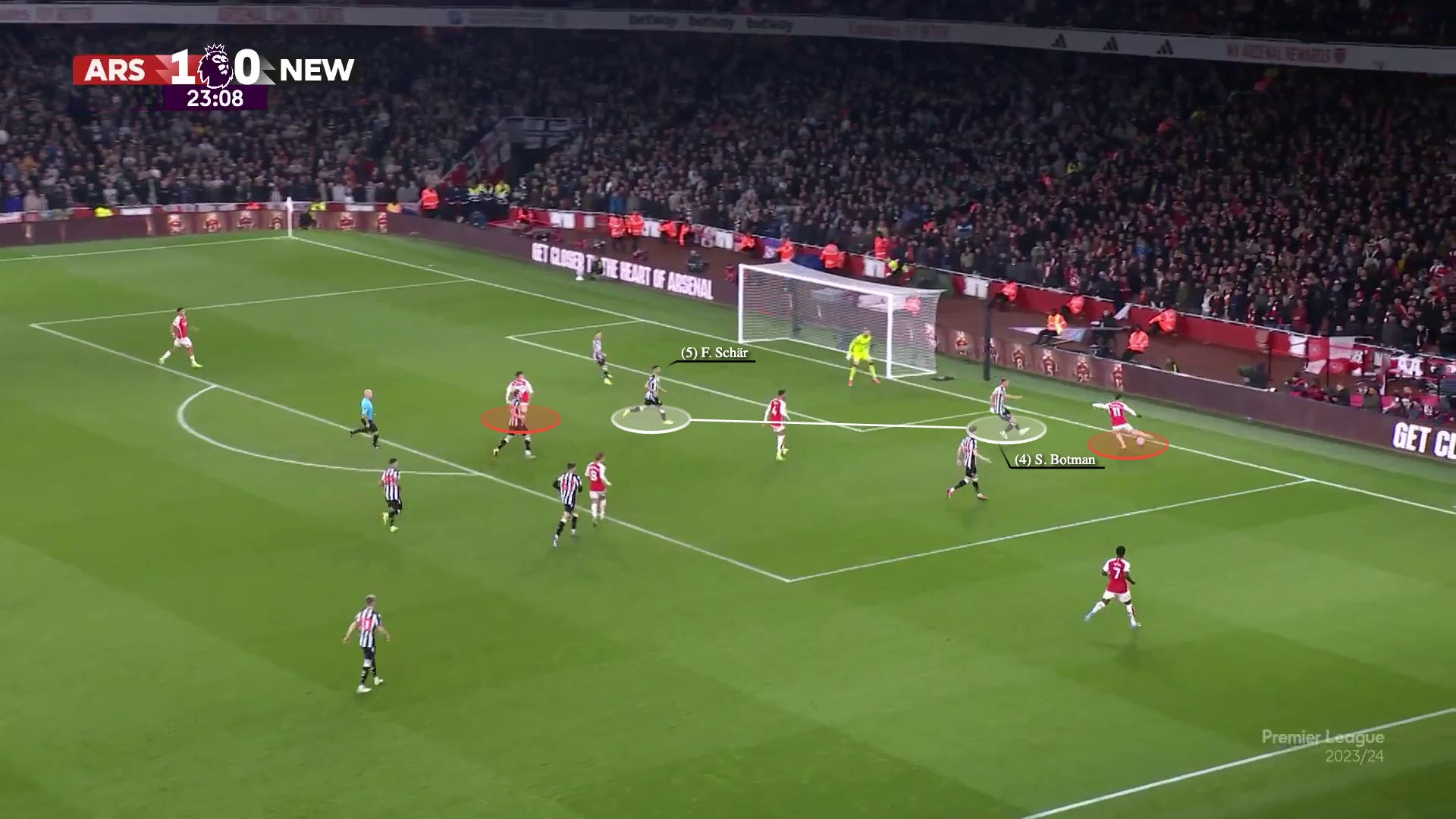

And here’s the “after” state — this is one pass later. That mid-block, with CB’s so compact and impenetrable, doesn’t look so compact now. Three handoffs made it so, from Tripper to Schär to Botman.

…and we must also pay quick respect to Kai’s movement in the box that sealed the deal. Watch him here.

He sees that Schär is going to get drawn down to the near-post, so he ghosts into his blindspot and then sprints through the middle. These little “peeling on” and “peeling off” motions are one of those subtle things that he’s immense at.

Here, we can watch the whole thing from the beginning.

So much of this is based on the quality of the pass, and it’s why so many of the highlights originate from some of the best passers in the world. But it’s also dependent on a specific advantage — in this case, Martinelli’s speed.

If you’re looking for a more easy-to-complete, grounded version, you still need a runner with some physical advantages.

The simpler version is this. I’m not actually sure where the final Fulham player is (😂), so we’ll ignore that for the moment — but you’ll see Haaland occupying one CB before getting over the shoulder of the other one. This can discombobulate them both.

Then, if you have another player who fills in that zone right after, you have a soft spot for the grounded cross. A big part of the rise of these strikery midfielders — Havertz, Jude, Álvarez — is based on this simple insight: having somebody fill in when a forward drags CB’s around.

You can see a similar move here by Hellas Verona against Roma.

Manchester United (hear me out) have a regular method for exploiting that area between the backline and keeper, as noticed by @ftblnatt on Twitter.

I don’t know anything about boxing, but I imagine some of that sport is about trying to punch your opponent as soon as they drop their hands.

There are natural moments of respite in a mid-block. Specifically, they are more likely to momentarily “turn off” when they believe the in-possession team is going to lazily recycle play in the back. Ten Hag looks to pounce on this weakness by building a trigger for that exact moment. When the first pass comes, both attackers make their runs, and the deeper CM whips the ball in behind on the first touch.

The other idea is to build in some mechanisms for inducing the backline to “turn off” like this. This can be a roll of the ball, or faking a pass elsewhere right before dishing it out. In any case, something that your attackers know and the defenders don’t.

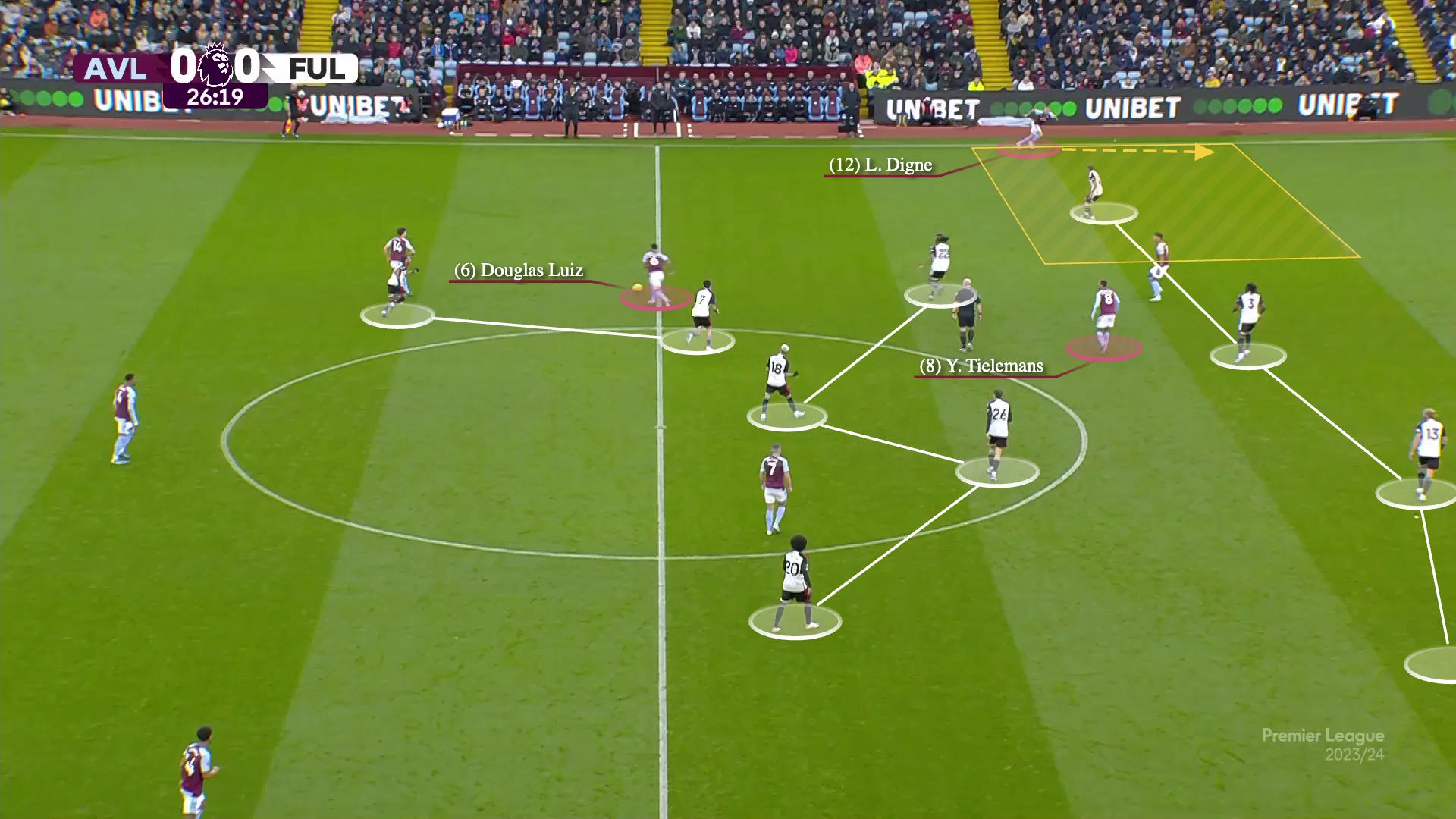

Here, you’ll see Luiz receive the ball and Digne prodding the wing with a run. As we’ve said before, this can be difficult to hit unless the wide defender is leaning forward, slow, or liable to be caught sleeping.

So Digne pulls up his run, and drops lower to receive. As the usual width-holder, Saka has been doing this more of late because it has the add-on effect of dragging the opposing full-back down (up?) the pitch. This now creates space to run in behind. Tielemans sees it and, despite not being the most fleet of foot, gallops that way.

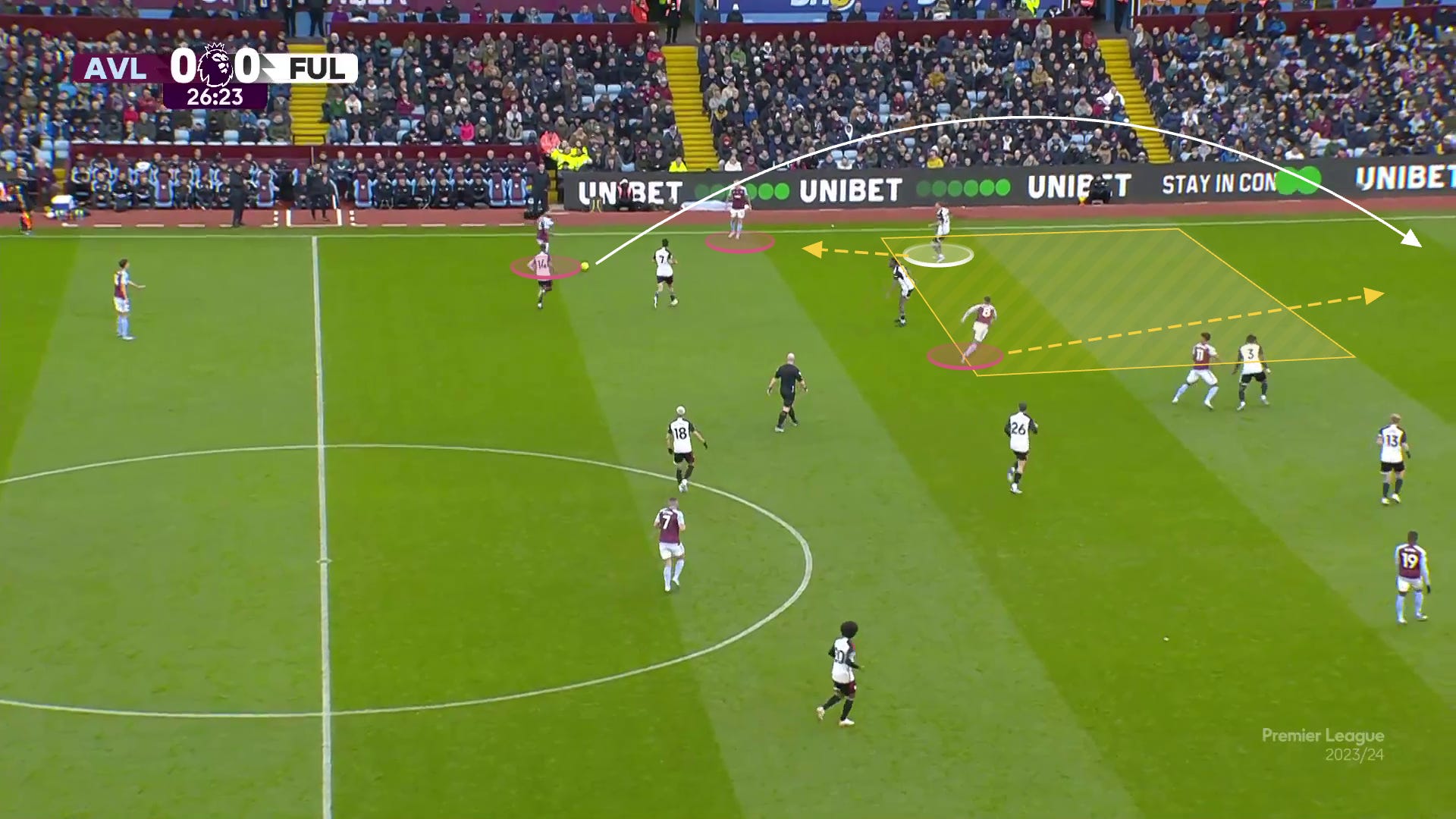

And here’s the result.

Those corresponding moments — the width-holder dropping and somebody running in the new space — are a recurring theme.

Pep and Arteta may differ slightly on how they approach the middle of the pitch in the attacking phase. Arsenal have generally been more content to ferry play out wide, especially early in the year. That has changed of late, with the team flooding the middle third with a rotating cast of “10’s,” but it still comes in waves, which may have as much to do with new personnel and an adjustment period as it does purely strategic reasons.

That said, here’s Pep on the importance of building through the middle.

“Many coaches say that to avoid opponent’s counterattacks, be careful about passing the ball through the middle of the pitch. Alright, they’re right. So if you don’t want to pass through the middle, you pass it to the touchlines. But it is impossible to play well unless you pass through the middle. Of course you can win games by playing like this. But when the ball is passed through the middle, the attacking players receive it ready with their bodies on their sides in an attacking position. If the ball does not pass through the middle, it will reach them from the front with the rival defender behind them. Of course if you lose the ball in the middle, it’s a risk, and you screwed up. But it’s a decision. Because it’s going to happen to you. You’ll lose balls in the middle. And the rival will score on counterattack. You will come home and question your idea. But on Tuesday, when you get in front of your players you will ask yourself: will I change my style? Or do I insist? Well, insist.”

The best, and simplest way to do it, is by finding (and creating) little gaps in the block. As we covered last time, this is the ideal situation — in which Ødegaard is open and able to turn after receiving it between the lines. But if the defending is good, this is not always possible.

Here’s another way I like. Below, you’ll see Rice carry it up, lay it off to Jorginho, and then change speeds and ghost between defenders to push it back. This is (obviously) more effective than him just standing ahead of the ball and hoping it comes to him.

You’ll see it here, too. Everything is crowded, but Martinelli has been floating around, and Jorginho simply finds him with a line-breaker. Nothing earth-shattering here, just good reads and passes, and small gaps available in the block.

Inter Milan may be the most fun team to watch in the world right now. They’re direct, adventurous, disciplined, and so incredibly well-coached.

For my money, the best part of watching them is seeing how they use their CB’s to gallivant up the pitch and unsettle blocks.

I mean, look at this from the Champions League. The three CB’s have become the three midfielders, and the two deepest players are a midfield duo.

It’s not always that YOLO, but that gives you a sense of how confident and assured they play all the time. I like it all for a few reasons.

Here’s an example last year of Bastoni floating up from the LCB position and whipping in a cross to the opposite wing-back.

This is also from last year, but it shows how these “unhooked” CB’s allow the midfielders to drop back and then arrive in the midfield with more speed, rotational coverage behind, and more attackers ahead.

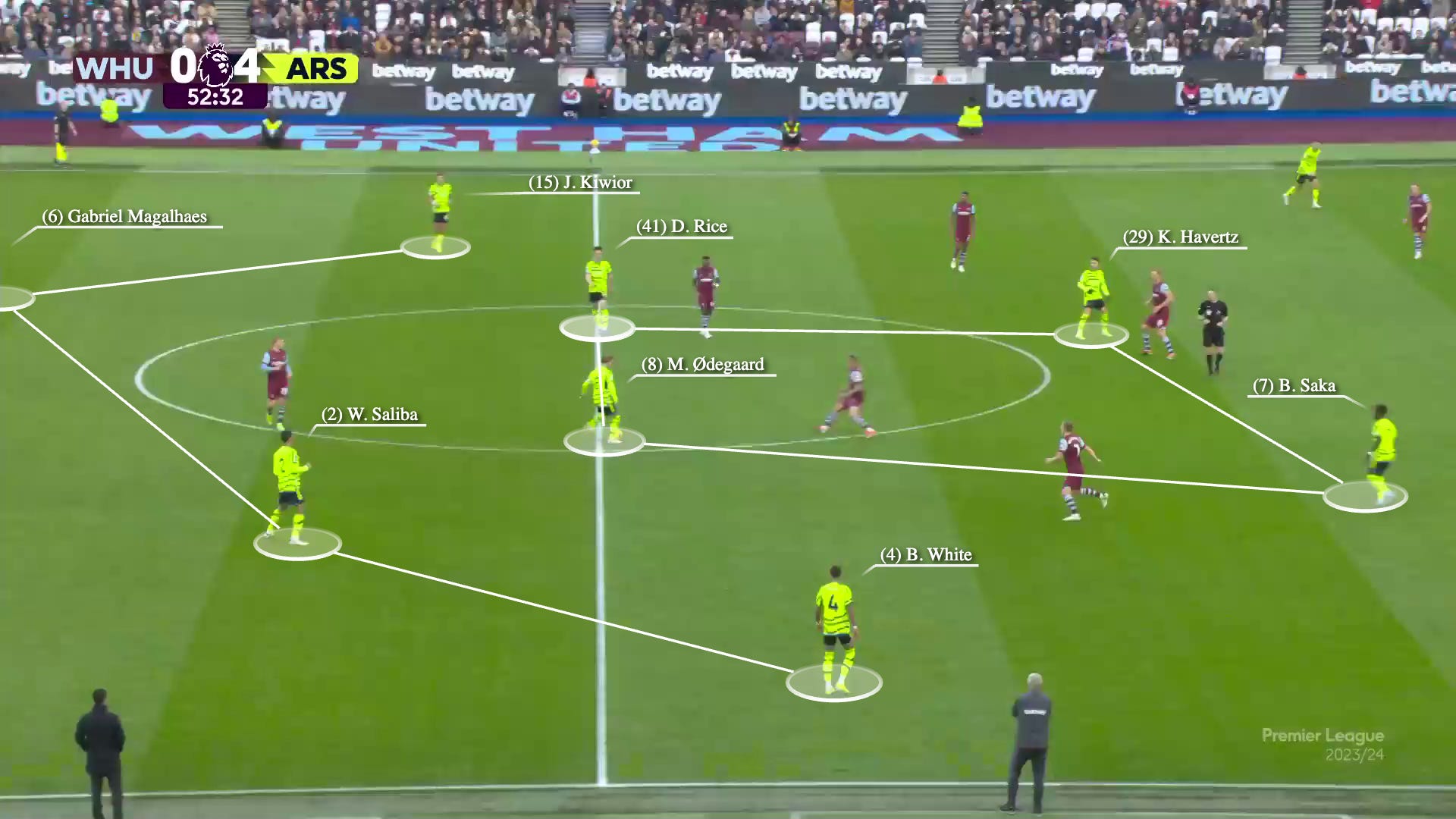

Arsenal have been tweaking of late. One of the more noteworthy changes since the break in Dubai has been some updates to the pivot in which White is joining more from the right-back, and Saliba has more freedom to roam. Ligue 1 naturally has better conditions for carries, but if you watched him back then, you’ll know that Saliba has some untapped potential as a dribbler and carrier.

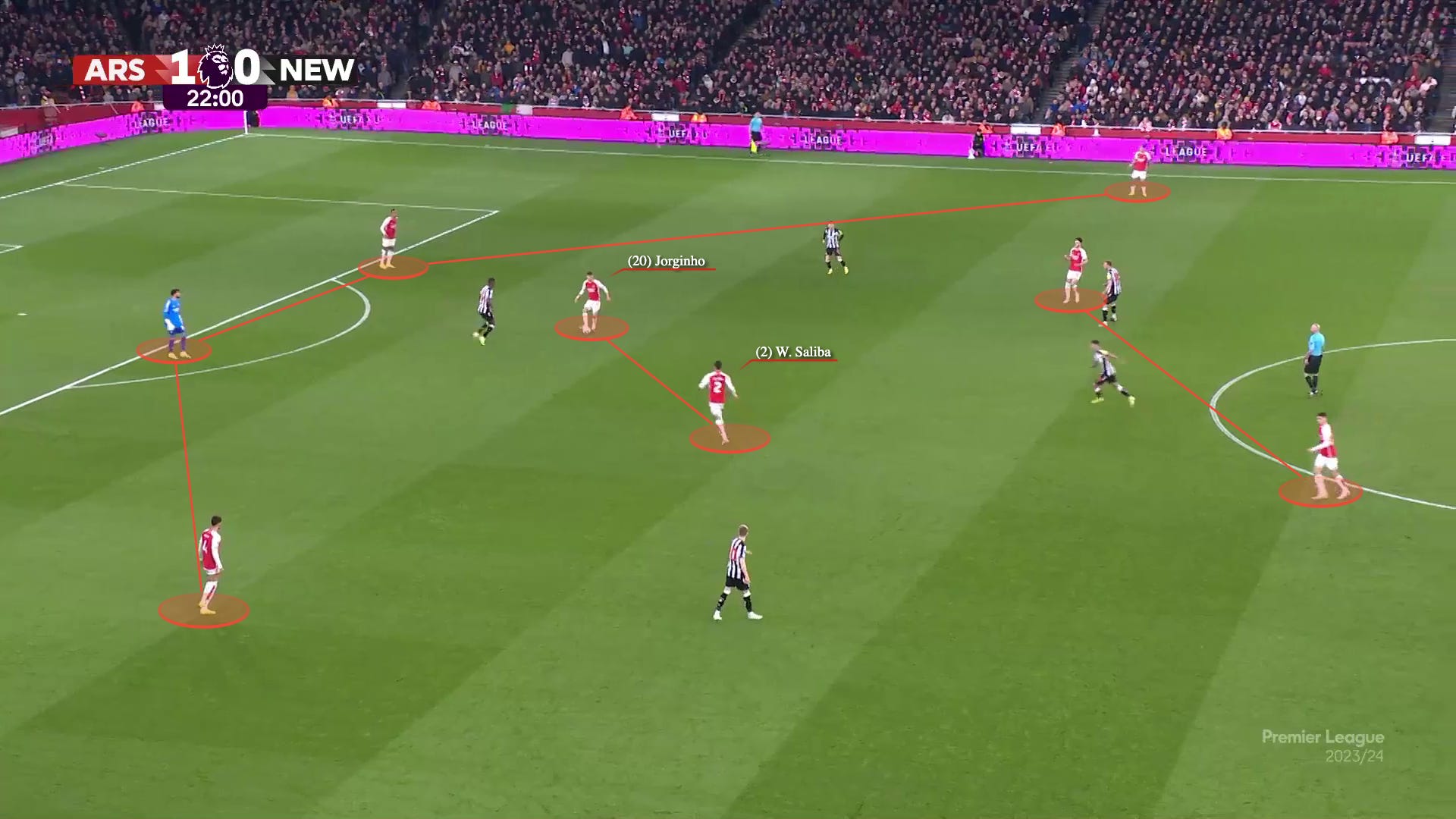

Here, Raya joins as the RCB, and it’s Jorginho and Saliba in the pivot.

Saliba is in a strength-versus-strength battle here: he’s awfully comfortable in 360° scan-and-turn situations in the midfield, but it’s a question of whether it’s worth sacrificing his ability to mop up everything in back to do it. For now, Gabriel is looking more comfortable by the day in being the deepest defender, which wasn’t always the case. It’s all interesting.

And here, in more of a momentary snapshot, you’ll see more of the advantage that this lineup brings. Raya becomes the extra man at RCB, Jorginho drops like Barella might, Saliba can stay wide, and another true midfielder (Rice) can bounce it out to Gabriel. There are just too many players to mark.

As we covered in the Porto preview, deeper carries are one of the best ways of unsettling a settled block. Those are most likely to be delivered by Rice, Saliba, and White — all of whom are pretty conservative on the dribble in their current roles (likely for out-of-possession reasons).

Here, you see Koundé dribbling to provoke and drag the Porto forwards over, which induces the “trigger” for them all to defend aggressively. Then, he goes against flow to pass it into the middle, and it’s quickly dished out to the wing.

There’s now an isolation for Cancelo. Goal.

So we’ve covered a few ways to break down a mid-block, some of them more novel than others.

In doing so, we may have missed my #1 method, which I’ve been asking for all year: the half-space cross. You’ll see it here: a wide dribble, played back to the half-space, with a curled cross to a blind side run to the far-post. This can be a full-back, but this is how Haaland scores so many of his goals. Havertz has these in him.

Here’s a long clip of that working over and over. It’s so difficult to defend: the back-line has to drop, then rise again, then track multiple runners in their blind spots while tracking the ball. Then, the far-post runner may head back into the mixer, causing more confusion. More, please.

Then there’s the wide overload, which is a primary storyline in any game against a mid-block, and probably deserving of its own post. The simplest way to look at it is having the CB carry up and join the wide attack as a +1. These numbers unlock interesting movements ahead.

Otherwise, here’s my other, brilliant method: get your best fucking players the ball a whole fucking lot. There’s the story of Chelsea regrouping to talk about nuanced, tactical ways of breaking down West Ham a few years back, and Eden Hazard, unaware of many of the players he was even facing, just replied that he was better than them and he’d beat them and score. They gave him the ball. He was right, of course, scoring twice.

Against Porto, there was a systematic failure to get Saka the ball. He is better than everybody. If you get him the ball anywhere, at any time, there’s a good chance of something happening — and his value becomes especially great when things are tougher for everybody else.

In that sense, this is one of my preferred shapes to doing that — Ødegaard receiving deep and Saka floating to the half-space, and Arsenal having a healthy appetite for risk about delivering balls to him. I think it’s fine to have Ødegaard drop all the way to the backline when the team is short on passers.

If that doesn’t work, have Saka drop wherever, whenever. Just get him the ball.

In the end, beating a mid-block is all about quality and physical advantages. Do the players on the pitch have the individual passing quality to unlock the block? Do the attackers have the quality in movement, and the physical advantages, to exploit momentary openings? Are there a few mechanisms from the training ground to bring to the big games?

What has been difficult for Arsenal has been difficult for many top teams. This year, it has been made especially hard thanks to injuries to key passers: Zinchenko, Partey, Timber, Jorginho, Vieira, and — yes — I’ll include Jesus in that category. That list hurt to type. The team is at its best against the top mid-blocks when one, two, or more of them are on the pitch. So many of these “rarer” passes can get hit by the players I just listed; the Arsenal double-pivot can go toe-to-toe with anyone.

Who knows “if” and “when,” but Vieira’s comp reel sure includes a lot of those block-busting passes you see from the top brass. It’s been a frustrating wait.

There are nuanced considerations about the best use of Havertz in these games, mostly about the specifics of the opponent and the availability of his teammates. He showed he can contribute at a high level in the LCM/SS role in the 11-0 combined score against the overmatched West Ham and Burnley, and he scored the late winner after coming on against Brentford.

But he also clearly looked better against Newcastle (at 9) than at Porto (when the team was one passer short). It seems obvious that the Newcastle setup should have been used at Porto, but we’re not privy to injury and fitness considerations. Oh well.

Arsenal vanquished Newcastle, and have been steamrolling league opponents throughout 2024. At the same time, Porto was humbling, and a stark reminder of how quickly fortunes can change. While many improvements to the mid-block attack have been implemented, they can still get better on the fringes.

Hope you enjoyed this all. I’m sorry for the headline, by the way.

Be good. ❤️