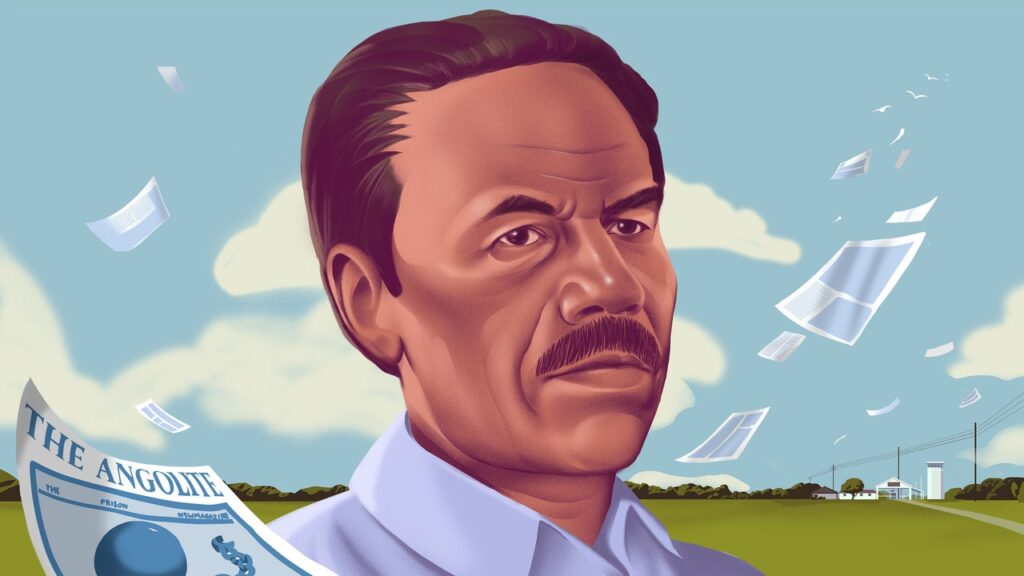

In 1961, Wilbert Rideau, a nineteen-year-old with an eighth-grade education, robbed a bank in Lake Charles, the small Louisiana town where he lived. During a botched getaway, he killed a teller named Julia Ferguson. Rideau spent twelve years on death row at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, or Angola, a former plantation that occupies as much land as Manhattan. Then in 1972, the Supreme Court struck down Louisiana’s death-penalty law; Rideau soon joined the prison’s general population. After trying and failing to get a job at The Angolite, an all-white prison magazine, Rideau created The Lifer, which may have been the first African American prison periodical.

The Lifer was shut down after only two issues. Rideau, however, started to freelance for regional newspapers, and even wrote a story for Penthouse about Angola’s Vietnam veterans. In 1976, when a reformist official named C. Paul Phelps became Angola’s warden, he named Rideau the new editor of The Angolite. “Phelps felt there was a role for freedom of expression and journalism in prison,” Rideau told me. “Censorship, and keeping everything a secret, was counterproductive to changing things.” The magazine had its own unrestricted phone lines, cameras, and tape recorders; Rideau often reported outside the prison with unarmed escorts, and, on two occasions, attended a convention of newspaper editors in Washington, D.C. He said at the convention that, even in an institution rife with violence and conflict, The Angolite “had proven valuable at easing tensions”—not only because it countered rumors with reporting but also because it helped “keeper and kept understand each other.”

Under Rideau’s leadership, The Angolite was nominated for seven National Magazine Awards. One of his stories, “Prison: The Sexual Jungle,” about men who raped and subjugated other men in Angola, won the George Polk Award. “The act of rape in the ultramasculine world of prison constitutes the ultimate humiliation visited upon the male,” Rideau wrote. In the seventies, American prisons still tended to aim for rehabilitation rather than punishment, and the story led directly to policy reforms. But, at a time when Louisiana’s governor commuted many serious sentences, Rideau was repeatedly denied release, seemingly because of his high profile. Only in 2005, after his murder conviction was overturned and he was convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter, did he win his release. Now eighty-two, Rideau has spent the past nineteen years with Linda LaBranche, who fought for his release and then married him, and several cats. He still works as a criminal-defense consultant.

On April 12th, the George Polk Awards, which honor a CBS journalist who was murdered during the Greek Civil War, named Rideau one of its career laureates. In advance of the occasion, I called him from the often stormy recreation yard at Sullivan Correctional Facility, in New York’s Catskill Mountains often exposed to the snow and rain. I found his story relatable: in my twenties, with a ninth-grade education, I was convicted of murder and given a sentence of twenty-eight years to life; I started to report stories after taking a creative-writing workshop in prison. Rideau and I spoke in the course of several weeks, during half-hour calls for which a prison contractor, Securus, charges $1.25. I asked him about his Southern childhood, the power of reading and writing, and his provocative case for professional relationships between prison officials and prisoners. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the first book you read on death row?

“Fairoaks,” by Frank Yerby—a plantation novel. I was totally shocked that something like this existed, because, you have to understand, the world I came from didn’t teach slavery to the students.

The first time you learned about slavery was reading Frank Yerby on death row?

On death row!

In your memoir, you wrote that reading allowed you “to emerge from my cocoon of self-centeredness and appreciate the humanness of others—to see that they, too, have dreams, aspirations, frustrations, and pain. It enabled me finally to appreciate the enormity of what I had done, the depth of the damage I had caused others.”

It’s why I’m such a pro-book person. It’s exposure to other perspectives, to other lives, to other beings, to other worlds.

You grew up in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

It was the Deep South—a totalitarian regime that was all about white men. As far as criminal justice goes, let me hip you to something. You’re a prisoner, and you’ve been through the system. But I come from a world before Gideon v. Wainwright. You didn’t have a right to an attorney. You didn’t have a right to anything except to complain, to pray, and maybe to die. At a certain point, because of Emmett Till and sensational stuff that was disturbing the country, they decided that lynching Black folks was bad for their public image. So they transferred what they were doing from the tree and the rope to the courtroom. In 1961, I was a product of that world. I was frustrated. I was angry.

At nineteen, you probably couldn’t wrap your head around all this.

I was really, really ignorant. I didn’t even know who the hell the governor was. And the crime, even in my own opinion, was really stupid. I tried to rob a bank, it got out of hand, and I panicked. I was scared. One of the tellers ended up dead. I killed her. I’m responsible for that.

Eight weeks later, I was tried by a jury of all white men, and in an hour they came back with a verdict of death. The United States Supreme Court threw out the death sentence, called it a kangaroo-court proceeding. In 1964, twelve white men again found me guilty and gave me the death penalty, in fifteen minutes. In 1970, a federal court threw that conviction out, too. And again, twelve white men found me guilty, this time in eight minutes. Three juries with all white men, in a state where half the people are women, and a third of the population was Black. That was justice back then. That’s why they called it “lynch law.”

I mean, we’re all so ignorant when we come to prison.

And a lot of us grow up like a weed in the crack in the sidewalk someplace—untended, unguided. Just on its own. That’s asking for trouble. I mean, the fact that some of us turn out to be a beautiful flower, that’s a miracle.

After the Supreme Court decision in 1972, when you got off death row and moved into the Louisiana State Penitentiary’s general population, you had to get a weapon, right?

Everybody did. The guys who were creative, we hung together to kind of protect ourselves. I try to explain to people that, in a lot of ways, sentencing me to death saved my life. Putting me on death row [initially] protected me from the violence in the prison.

You started pursuing writing ventures. You couldn’t get a job with The Angolite, so you started The Lifer. What did that look like?

We put together the paper at night. I was a commissary clerk. I’d hook up the electric typewriter, and other guys in different offices would type up articles. I had this contact; he was a gangster, and he would let us use the copy machines. They wanted a little money, and we took care of that. They’d print it out, and we’d take the sheets to an empty place, usually the education department. We’d have different lifers pulling them together, stapling them, and binding them into magazines. After that, we had people who took them over to the different prison camps.