Many of us are driven by productivity and do not take our own need for rest and recovery seriously, says clinical fatigue specialist Vincent Deary. (file image)

Photo: 123rf.com

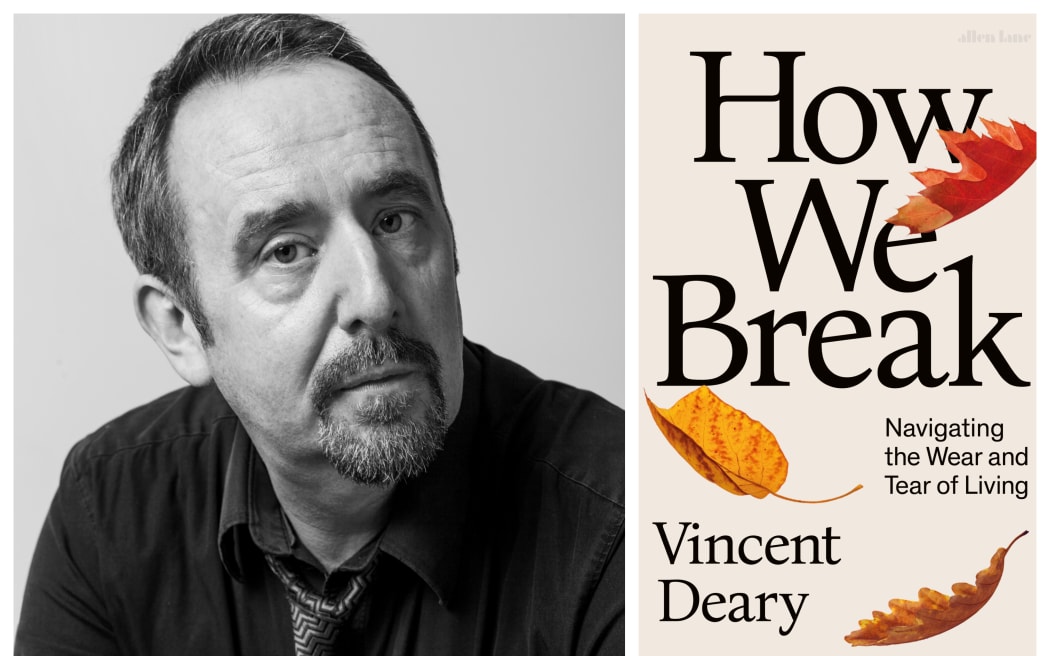

When recovering from burnout it helps to prioritise doing whatever restores your spirit, says clinical fatigue specialist and “really skilful worrier” Vincent Deary.

“I would encourage people out there, particularly people who are feeling ground down at the moment, to start valuing and practising the stuff that actually put some fuel in the tank,” he tells Susie Ferguson.

In his new book How We Break: Navigating the Wear and Tear of Living, Deary writes about how learning to rest helped him recover from post-viral fatigue which had him laid low for a year.

Many of us are driven by productivity and do not take our own need for rest and recovery seriously, he says.

“Rest is hard work for a lot of us. We don’t really know how to rest and recover. It’s not something that we’re taught or something that we value.”

Often it is an accumulation of stressful events over time which lead people to burnout, Deary says.

In the modern world, where we are very good at ‘being on’, many of us view rest as something to do only after “the important stuff”.

Yet being on too much without a break wears people out mentally, emotionally and also physically, Deary says.

“Your immune system will begin to change, your cardiovascular system, your digestion, your whole body will begin to become a bit dysregulated if you go on having that kind of demand for too long.”

In How We Break, he writes about how his own body started to shut down after two years of too much going on for too long – job pressure, viral illness and heart trouble.

“We all break in our own way and for me it was fatigue. For other people, it might be worry or it might be addiction or it might be gambling or it might be a combination of different things.

“I was just laid low physically, and also my moods began to be affected by that as well … I got very low and quite hopeless.”

When Deary ran out of gas completely, he had to learn to do what he helped other people do – be kind to himself.

“It’s really easy to tell other people to do that and it’s really difficult to enact it for yourself. Still valuing yourself and being kind to yourself when you’re not able to do a lot of the stuff that you’ve previously valued yourself by – that’s something I had to learn.”

Working at a fatigue clinic, Deary helped exhausted people challenge their personal beliefs about rest and recovery.

“They would believe rest is a luxury, rest needs to be earned, rest is for weak people, strong stoic people don’t need to rest to recover.”

Allowing ourselves to rest deeply is hard work for a lot of us, he says.

“We don’t really know how to rest and recover. It’s not something that we’re taught or something that we value.”

Deary helped his own recovery from fatigue by paying close attention to the things which nourished him and the things which depleted him.

“I began to gradually get back into doing stuff, I began to pace myself better. I began to pay more attention to stuff like joy, nature, stuff that actually put some energy in the batteries.”

Prof Vincent Deary

Photo: Jochen Braun

What enables someone to feel a sense of rest and recovery could be time in nature, painting or meditation, Deary says, and we all need to experiment to find out what it is for us.

“What genuinely pushes the off button? What allows you to feel that feeling of deeply physiological embodied safety when you just have that deep out breath and genuinely switch off?”

While there are different ways to recovery, we first need to value positive states as both the end goal, he says, and “biological necessities”.

At a 10-day silent retreat recently, Deary – a self-described “very skilful warrior” – worked on deliberately trying to evoke and sustain feelings of joy and relaxation.

“I could worry myself to death and frequently nearly have. It’s something I’ve practised my whole life. But I haven’t practised joy, peace, curiosity.”

For Deary, it was a revelation these states of being can be learned – with practice and only once we start valuing them.

“I would encourage people out there, particularly people who are feeling ground down at the moment, to start valuing and practising the stuff that actually put some fuel in the tank.”

Our internalised productivity drive – the idea that we are only okay if we have done this or finished that – can be a barrier to feeling that it is safe to rest, Deary says.

It can help to practice saying to yourself something like ‘Actually you are okay just as you are and I’m going to treat you with the kindness that I would treat a friend who is struggling at the moment’.

Although most of us find it much easier to be kind to others than to ourselves, he says, and resting requires some self-compassion.

“If someone came to us who was struggling and exhausted and worried and anxious, the first thing we would say is take a break. What can I do to make you feel safe and relaxed for a bit? It’s doing that for ourselves.”