She described the talks as “very interesting”, adding that it reflected China’s emergence as a global space leader.

“When you are powerful, people come to you for negotiations. Before, no one would come to talk about these issues,” Li said.

“When landing on the moon was just an exclusive US technological capability, [the US] didn’t have to think about the ownership of minerals on the moon or who would destroy its historical sites.

“Now that China has the capability to land on the moon, the US has suddenly realised that these issues need to be discussed and that’s why these concerns are surfacing.”

In 2020, the United States passed a law called the One Small Step to Protect Human Heritage in Space Act to protect American landing sites on the moon, but it only applies to the small number of companies that work with Nasa.

The Yutu – or Jade Rabbit – is named after the animal that in Chinese myth lives on the moon with the goddess Chang’e, after whom China’s lunar programme is named.

It landed on the surface of the moon in December 2013, becoming the first rover to operate there since the Soviet Lunokhod 2 stopped operating in 1973.

The Chinese rover survived for more than 900 days, well beyond its expected lifespan of three months.

Its successor, Yutu-2, then became the first rover to land on the far side of the moon in January 2019. It is still operating, making it the longest-lived of all lunar rovers.

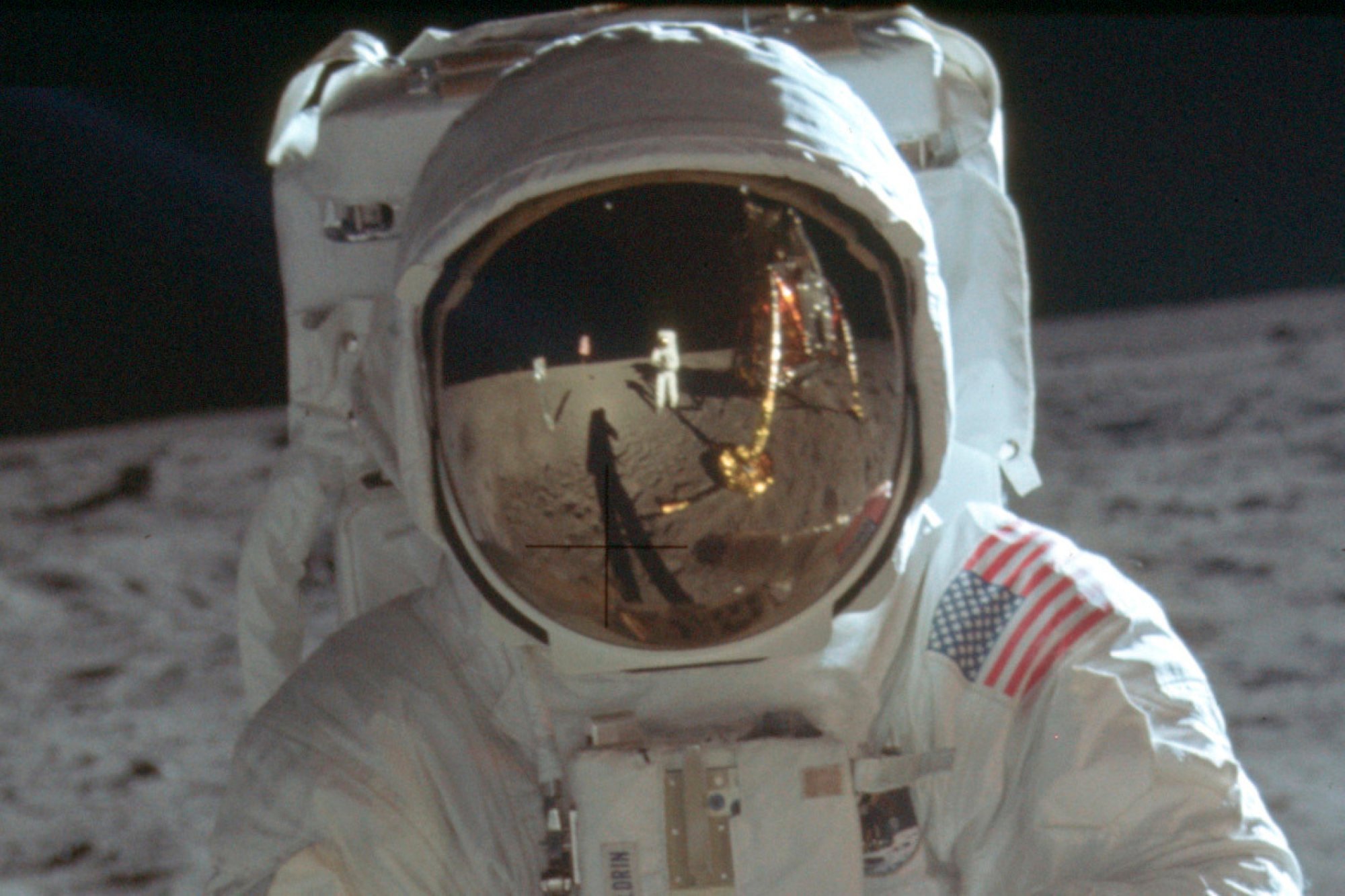

China and the US are also racing to be the first country to send astronauts back to the moon since the Apollo programme ended in the early 1970s.

But while the space programme is an enormous source of national pride in China, it has also attracted a strain of conspiratorial nationalism.

It pointed out that the social media frenzy was based on people misunderstanding a garbled comment made by a lunar scientist during a live TV interview and there was plenty of evidence, including several kilograms of samples collected by Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, to refute it.