I shared a humanities reading list two days ago. And it set something off.

Sure, it’s easy to come up with a list of books. But I set a much tougher goal. I wanted to offer a full immersion in arts and culture that

-

Only requires 250 pages of reading per week, and

-

Can be finished in 52 weeks.

The response has been scary good. I’ve gotten more positive feedback on this than when I write about pop culture—or even Taylor Swift! More premium subscribers signed up in a single day than usually happens in a month.

That just goes to show: If you give people a choice between Instagram and Socrates, they will chose Socrates. At least some people do in our little community.

Maybe Plato was right when he said that all things aspire to the good.

Or maybe something good is stirring in our culture at large. More people are starting to rebel against pre-fab culture by corporate mandate.

Maybe the humanities really is coming back, as I (and others) have predicted.

People are clearly hungry for an alternative to the intensely rationalized and techno-bullied tone of contemporary life. They want something deeper than algorithmic feedback loops and regurgitated chatbot chatter.

Am I dreaming? I don’t think so.

Many have asked me to enhance my humanities program with Zoom lectures and other educational supports. Alas, I just don’t have the hours to do justice to this.

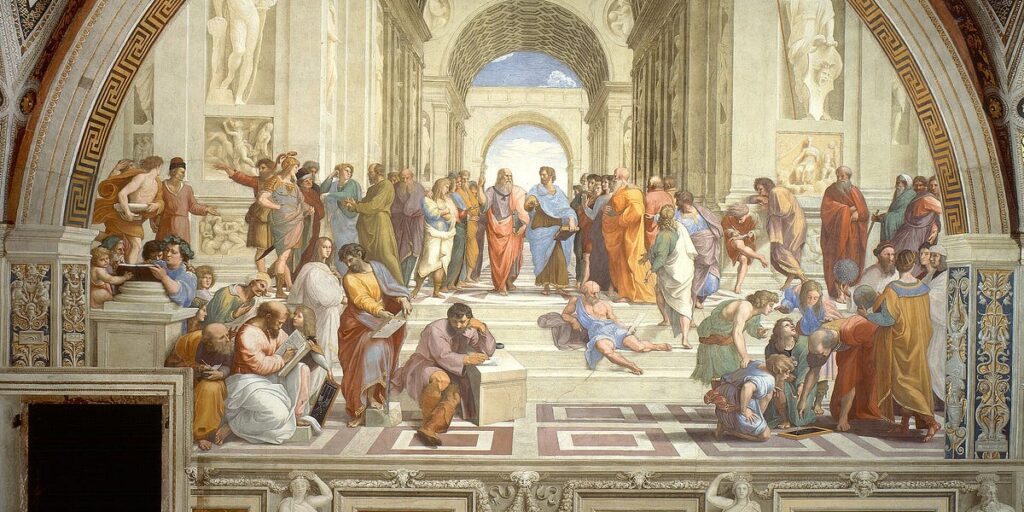

Yes, there’s just me at The Honest Broker. I don’t have assistants or interns, and I certainly don’t have my own School of Athens. I’m always operating flat out like a lizard drinking (as my Australian friends say).

So I’m suggesting that readers form their own discussion groups. Feel free to use the comments section below (or Substack Notes or chat or other forums) to set these up.

Perhaps some of you can volunteer to organize or host online groups.

Also seek out the many online resources for readers of these works. Please share suggestions for those, too, in the comments.

I am offering some reading notes and discussion questions (below) for the first week in the program—which focuses on the final days of Socrates, and also offers a glimpse of Plato’s Republic.

My hope is that this offers some sense of how I approach these works—which is a little more personal and immediate than what you might find in a college classroom.

Socrates was executed by the authorities—he just asked too many questions. But the official charge was corrupting the youth.

Socrates taught youngsters to ask questions too—including a smart kid named Plato, who later wrote about it. That was sufficient reason for a death sentence.

Just think that over for a moment, and consider how disturbingt it is—namely that the wisest person in ancient Greece was killed for his contributions to Western culture.

Tell me how I should react to this. I only see two options:

(1) The story of Socrates is a positive for Western culture—it proves that the system stirs up constructive criticism from within. We are better because we develop wise visionaries who challenge the system, even if it puts their lives at risk.

Or

(2) The story of Socrates is a negative for Western culture—it proves that the system is rigid and intolerant. It will kill anyone who challenges the power elites, even if that means executing the wisest person on the planet.

Tell me which of these conclusions is correct. Or maybe they are both right—but how can that be so?

Can you really educate people just by asking questions? (Hey, that’s what I’m doing myself, right now.)

Socrates thought so. They now call it the Socratic method.

Everybody praises it. Everybody admires it.

But almost nobody actually uses it in the classroom. (There are a few exceptions—such as Harvard Law School—but more than 90% of teaching ignores the Socratic method).

Why is that so?

I have some ideas. Maybe asking questions is not a useful way of teaching? Or maybe the Socratic method is still too threatening to entrenched power elites (just like Socrates found out himself when he was put on trial.)

As soon as you start asking questions, you have an obligation to listen to the answers.

Do we want that? Should we want that?

Help me readers! I think I hate Plato. But I also sorta love him.

I’m turning to you for advice.

Plato was the first person to imagine a system of government—his Republic—which was built on reason and logic, not politics and power. That’s an amazing thing, no?

But I would hate living in Plato’s Republic. For a start, he gets rid of a lot of music and poetry. How could I live in that neighborhood? And his system of government feels very authoritarian and sometimes almost tyrannical.

I get especially suspicious when he decides that we need to eliminate kings and other political bosses, and replace them with (guess what!). . . philosophers like himself. Is this really an ideal Republic, or just a power play by Plato?

So I’m asking you, dear reader, for guidance. Can I trust Plato? Do we want a system of government created by philosophers? And run by philosophers?

On the other hand, if we get rid of reason and logic in politics, isn’t the alternative much worse? So maybe we should stick with Plato, and let him do his thing.

What do you think?

Plato claims in his Allegory of the Cave that there is a higher reality that we fail to see in our day-to-day life. Most of us only perceive shadows.

That higher reality has many names—philosophers call it the Platonic Forms or Platonic Ideas (or Ideals).

At first glance, this seems like a crazy notion. What could be more real than what I actually see and feel and hear in everyday life.

What in the world was Plato talking about? Or maybe what he is describing is not in the world? But if not, where is it?

Can I take Plato seriously? Or is this just another example of a smart person going off the rails?

As noted above, Plato says all things want to be good—even human beings.

This also seems a bit of a stretch. So many bad people are doing bad things.

But I also feel that Plato is correct—or, at least partly correct. And you must feel that too. After all, why would we even be reading Plato nowadays if we didn’t feel some inner urge to a better way of life.

So let’s help each other grapple with this. Why are we reading books like this? What can we get out of them? If we are really aspiring to the good, how do we nurture this inner urge and make it manifest in our own lives?

Okay, that’s how I would lead a Plato discussion group. And those five questions should keep things lively.

They are big issues. And the very fact that we argue over them—and have been arguing over them for more than two thousand years—testifies to the value of these readings.

Let that be a guide to the discussion in future weeks. Try to identify the ways in which these works challenge our own lives, and force us to analyze our own aspirations and values.

Don’t be afraid to view these thinkers from the vantage of your own hopes, dreams, and priorities. That’s often the best way of approaching these works.

By the way, this is also the best way of remembering what you read. Almost everything I remember about the great authors relates to how they made me think about my own situation, my own challenges and concerns.

If I was forced to give a spontaneous lecture on Plato or Aristotle or Shakespeare (or whomever), I would immediately start telling people what their works mean for me.

If I did it any other way, I would stumble. I’d get dates and facts wrong and give a terrible lecture. But when I draw on my own deeply held values and convictions and my own life experiences, it’s easy to talk about these books—and channel the power they possess.

We want to talk about them in that personal way. We need to.

If you approach these authors in that spirit, you will extract the most important things from their works, and will recall it for decades. And, even better, the course of your life will have been tangibly altered by having made these books part of it.

Plato actually promises that. We aspire to the good only after knowing what the good really is—and that’s exactly what he’s trying to deliver in our readings for week one.