B2B content contains a Catch-22:

- You need to write for search to justify the expense to produce an evergreen asset that will grow long-term ROI, but…

- You also need to write for a sophisticated audience to build credibility to ever eventually see said ROI.

Most brands skew too far in one direction or the other.

Write primarily for search and you get derivative, regurgitated, copycat content that immediately erodes trust with discerning prospects.

Write only for prospects, however, and your content is ephemeral – forever relying on short-term bumps in referral traffic that get forgotten within a week.

Semrush has somehow managed to bridge this divide for over a decade. Their year-over-year revenue was up 21% in Q1 of 2024, while growth in large customers paying $10,000 annually is also up 32% YoY.

In this article, Semrush’s Managing Editor, Alex Lindley, shares how his three S approach – structure, skimmability and search intent – can fuel SEO growth, plus helpful examples and takeaways.

1. Structure: Answer search intent without delaying the ‘time to value’

Writing for search and readers is a delicate balancing act.

On the one hand, you need to entice readers by setting up the problem and illustrating symptoms before providing alternative solutions.

On the other hand, you need to clearly answer search intent and structure articles similar to what’s already ranking so you can have a shot at evergreen traffic.

Nowhere is this conundrum more obvious than during the editing stage. An editor might think the paragraph and phrasing is the issue, while the underlying root cause is actually a poor article structure to begin with.

You can think of this “structure” problem as twofold:

- You spend too much time talking (or writing) about stuff that doesn’t matter, while also

- Not spending nearly enough time on the stuff that does.

Lindley starts with classic journalism advice, structuring articles in an inverted pyramid to help increase the “time to value” readers will receive.

- “For content the writer is creating for SEO purposes, I always point to the inverted pyramid and/or the bottom line up front (BLUF) framework.”

- “The reason is simple: The single biggest mistake I see writers make is delaying the time to value by adding too much exposition before getting to the point. Delaying the time to value essentially negates any attempt you make later to address search intent because a huge number of readers won’t stick with you long enough to see if you ever do get to the information they’re looking for.”

- “I realize, however, that this approach can alienate some readers – and, importantly, writers I’m working with – who prefer a bit of narrative or simply love language and writing for writing’s sake. Balancing strong structure and search intent with narrative and the “delight” factor is tricky, but when there’s any doubt, I always recommend leaning on BLUF first and everything else second. It’s the best possible approach when you’re not entirely sure of the best approach.”

This advice is especially relevant for long-form B2B content.

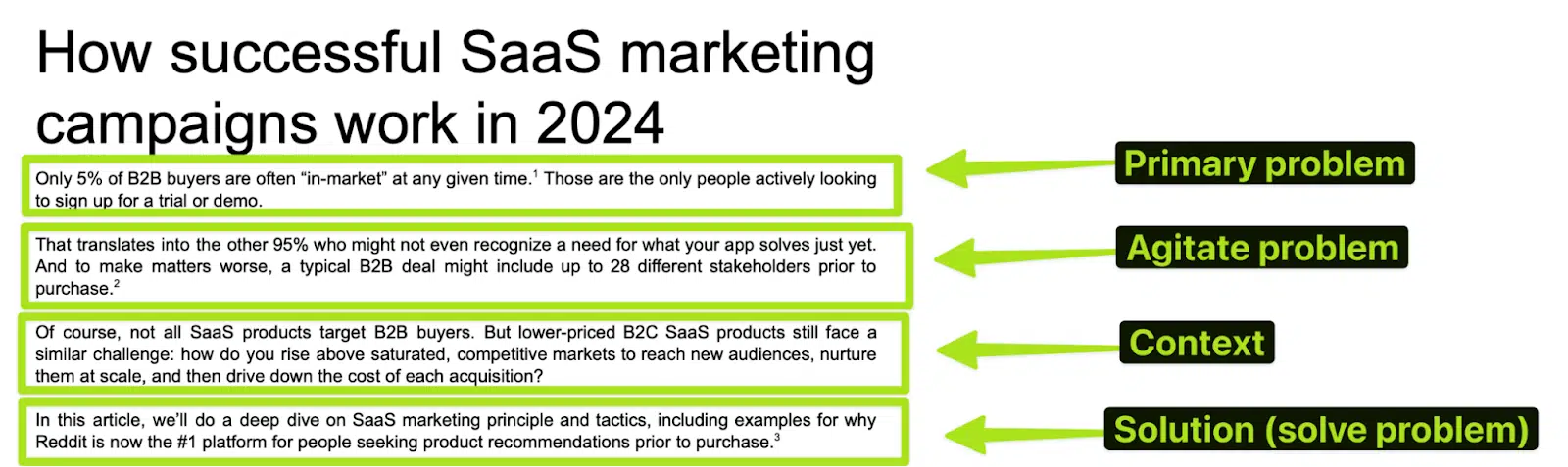

The decades-old Problem, Agitate, Solution (PAS) copywriting framework helps set context. You want to provide some background commentary so the reader immediately understands and resonates with the point you’re making, so that the ultimate payoff (or “solution”) hits that much harder.

The problem is that you might take too long to get there.

The trick, then, is to get in and get out – ASAP! Concision is the name of the game.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the only “structure” issue that causes concern.

Delaying the “time to value” is increasingly common because that’s how more and more “search”-driven content is being structured.

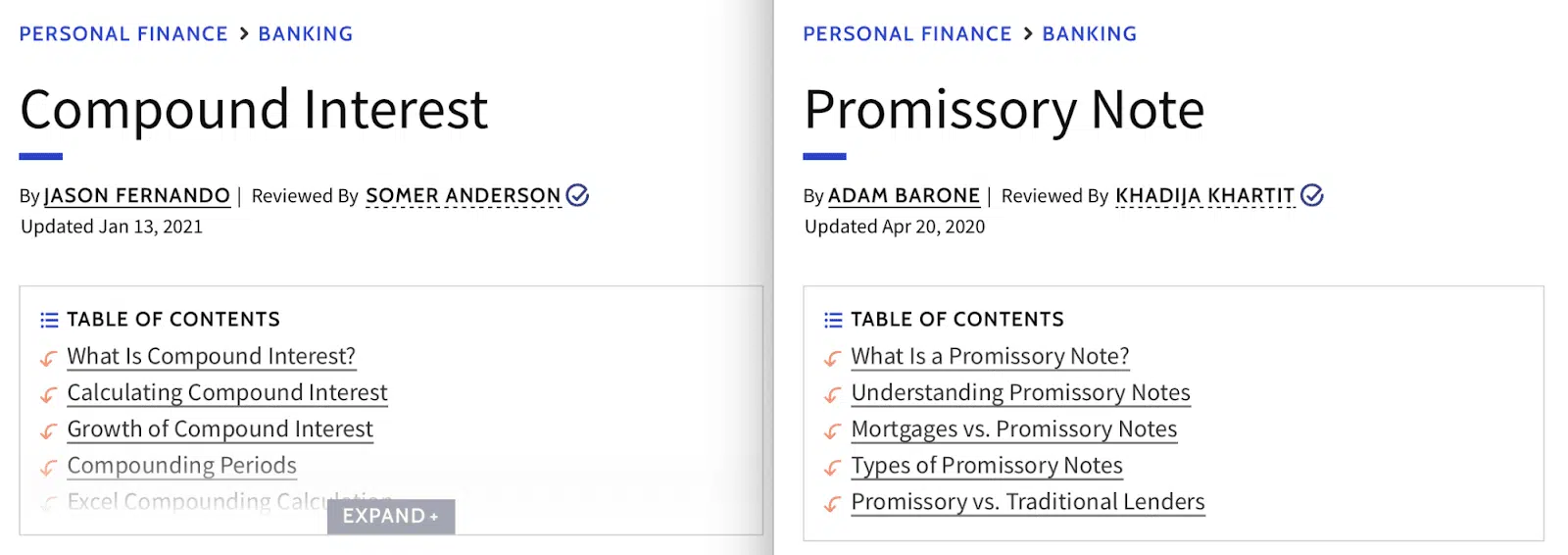

Look at the two side-by-side Investopedia examples below. Both are glossary or definition-based content, so notice the similarity in the heading structures used across each:

Another way most search content falls flat is by spending too long on the initial sections of an article (the “what is” or “why it’s important” sections) while not spending enough time answering the primary query behind the article.

- “The No. 1 biggest red flag I see with article structure is a compulsion to do the “who, what, where, why” in massive sections before getting to the meat of the article,” confirms Lindley.

- “For example, you have an article titled ‘Top SEO Tools for 2024.’ Then the structure looks like this:

- H1: Top SEO Tools for 2024

- H2: What Are SEO Tools?

- H2: Why SEO Tools Are Important

- H3: Reach a Broad Audience

- H3: Save on Advertising Costs

- H3: Make Data-Driven Decisions

- H2: How to Choose an SEO Tool

- H3: Consider Your Budget

- H3: Compare ‘Must-Have’ Features

- H3: Test Them

- H2: 11 Best SEO Tools

- H1: Top SEO Tools for 2024

- “We get 1,500 words or more in before we’ve even gotten to the point of the article. How many readers will sit through that or even scroll that many times before they get to the part they came for? Very few.”

- “Unfortunately, this kind of structure is really common online. It’s a search intent and time to value problem. And it often comes from either believing that search engines ‘want’ to see that kind of thing or feeling the need to reach a particular word count.”

- “But we simply don’t need to do that. In fact, we really shouldn’t if we aim to keep readers engaged. If the title promises something, give that thing to the reader right away. Don’t delay; don’t clear your throat. Just put it front and center. And if you need to cover the tangential whys and hows, do that later on.”

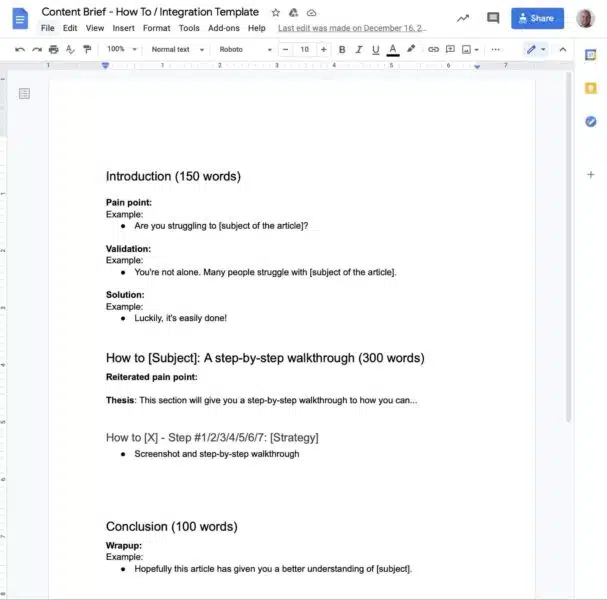

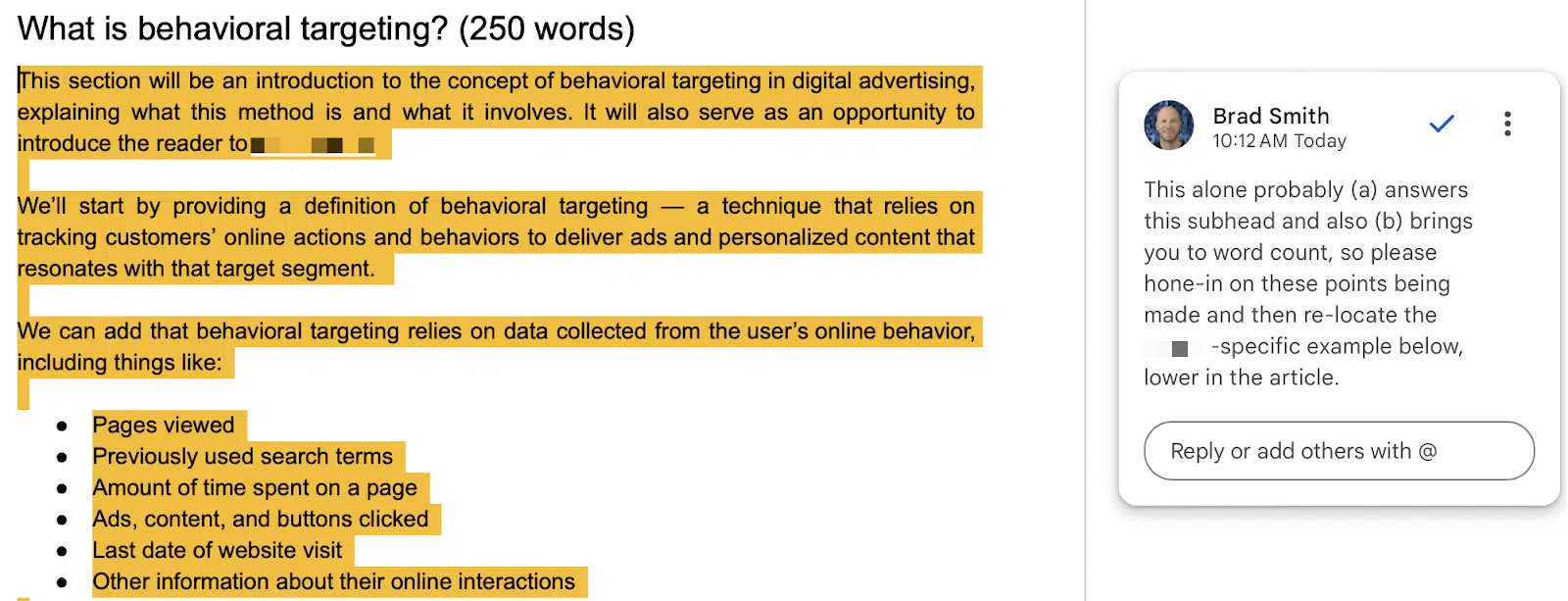

One way to mitigate this is to structure content in briefs and outlines with predetermined word count max ranges.

That way, you might still want to include the “what is” section to define a topic for search intent, but then remind writers to quickly move down to spending more time (or word count) on the sections that matter most.

A final tip on article structure and the subheading organization underneath is parallelism. Here’s how Lindley thinks of it:

- “Headers – the building blocks of article structure – should always be parallel. Listicles make an easy example. Here’s the ‘bad’ way to approach it, compared with the ‘good’ one right after.”

- H1: 3 Content Writing Tips

- H2: 1) Use Short Sentences and Paragraphs

- H2: 2) Read It Out Loud Before You Publish It

- H2: 3) Nailing the Search Intent (bad example)

- H1: 3 Content Writing Tips

- H2: 1) Use Short Sentences and Paragraphs

- H2: 2) Read It Out Loud Before You Publish It

- H2: 3) Nail the Search Intent (good example)

This last point seems small and nuanced on the surface. But as you’ll see in the next section below, it actually has a huge bearing on how “skimmable” the content is overall and whether you’re keeping the reader engaged to the end of the content.

2. Skimmability: Provide contextually relevant examples without interrupting the reading flow

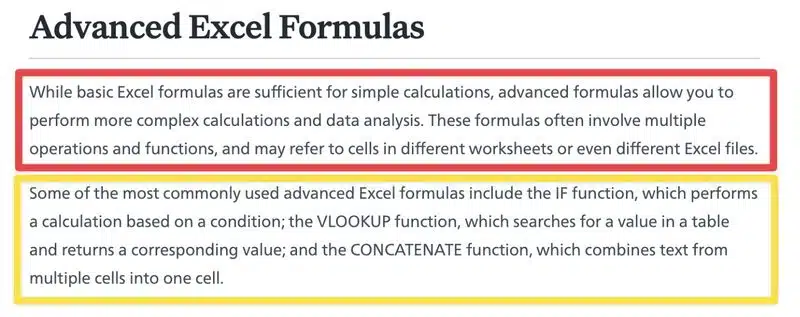

AI content can tell you what “advanced excel formulas” are, as evidenced by this sample below:

However, it’ll never:

- Show you advanced Excel formulas.

- Explain why they matter for who they help.

- Illustrate how to create advanced Excel formulas.

- Put them into a usable format like a free template or tool.

You future-proof SEO by avoiding head-on competition with what AI can do well. And instead you do what AI can’t do.

Backing up points being made in an article helps the reader visualize what you’re describing and increases the credibility in your claims.

It also arms your content with differentiation that other publishers can’t match.

- “The context part is often lacking in web content,” explains Lindley.

- “Many web publishers will throw a faintly relevant image at the top or bottom of a section and call it done – almost as if they’re working from some kind of checklist. But we need to aim for a higher level of helpfulness.”

The trouble is that knowing how to incorporate good examples always throws writers and editors for a loop. Thankfully, Lindley has a good framework to keep in mind:

- “Concept > Context (for the image or example) > Image or Example.”

- “In other words, start with the concept you’re introducing. State it plainly. Then, provide context for the example or image you’re about to introduce. Then include the example or image.”

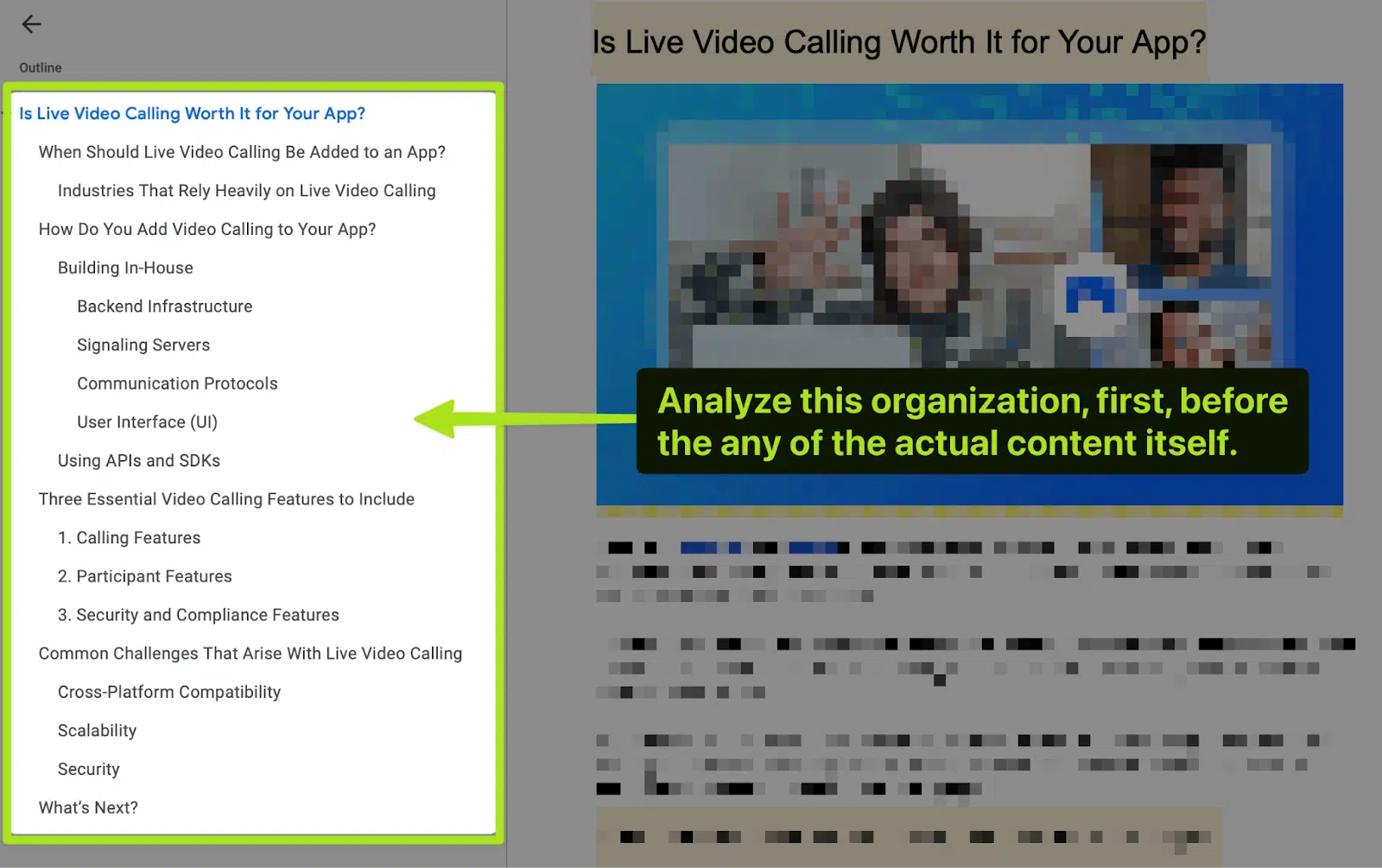

The second major skimmability issue can actually be spotted well in advance, prior to ever reading a single line of the content itself.

Go back to the overall structure again!

- “One skimmability problem that is easy to illustrate with examples (and highly applicable to many web writers) is when you’re unable to understand what a section or article is about from just the header title(s). That’s why I always look at the table of contents or stacked headers on the left side of the Google Doc before I start editing an article.”

In other words, start by familiarizing yourself with what is being proposed, the nested information under each section, and how these sections build on top of one another to get a general sense of the problems, challenges or examples that will ultimately be most appropriate later on.

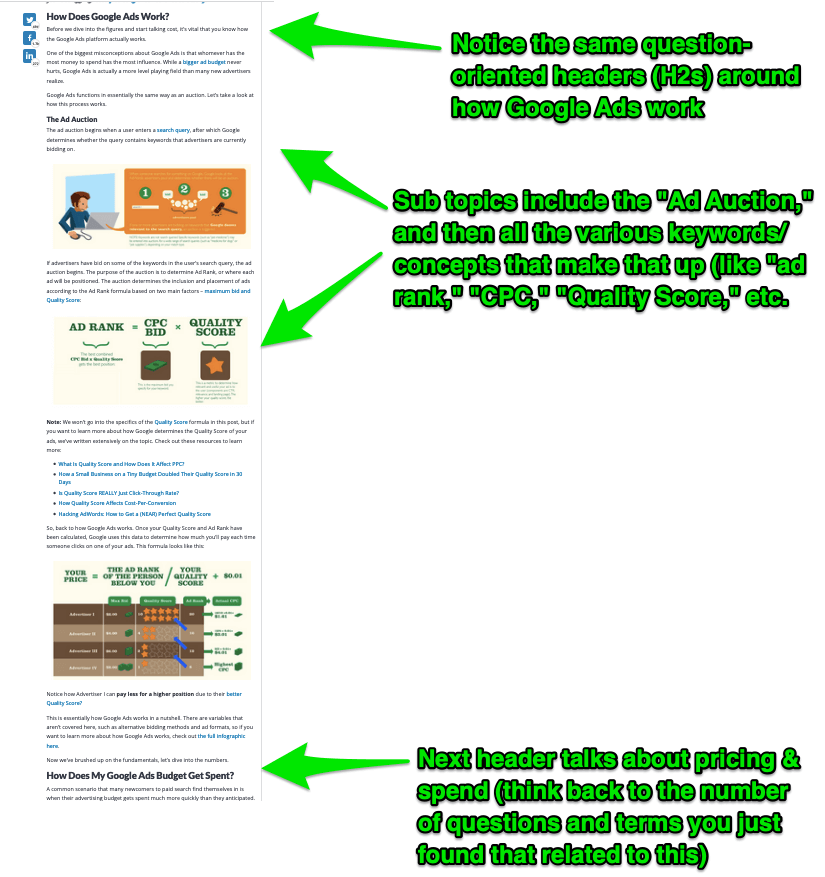

Lindley continues this example with another one:

- “For example, if I see the H2 ‘Content Marketing’ in an article titled ‘Types of Digital Marketing,’ I am pretty sure that section will describe how content marketing is a type of digital marketing. But if I see the H2 ‘Fire Up Your Keyboard’ in that same article, I’m confused, and I know there’s a problem.”

How do you know whether you (or your writers) are on the right track?

Again, back out of the actual paragraphs to take in the proposed article as a whole.

The table of contents or header structure can help, as can literally minimizing the text sizing in your browser to zoom out and consider all of the content together, like so:

Last but not least, here are three additional “don’ts” Lindley recommends following to help avoid interrupting the reading flow or risk losing the reader:

- Don’t make the reader squint to look for details in images that help them understand what they’re looking at.

- Don’t make them scroll back up to the paragraph text to look for help understanding what they’re looking at.

- Don’t make them read your explanation below the image or example and then go back up to the image or example to finally understand it.

3. Search intent: Focus editing on reader clarity, less on phrasing or semantic keywords

Over the last decade of working across hundreds of brands, I’ve noticed that good writers often make bad editors and terrible content managers.

The reason comes down to a skill set mismatch, where good writers excel at ingenuity and saying the same things in different ways, while good editors instead laser-focus on consistency and clarity.

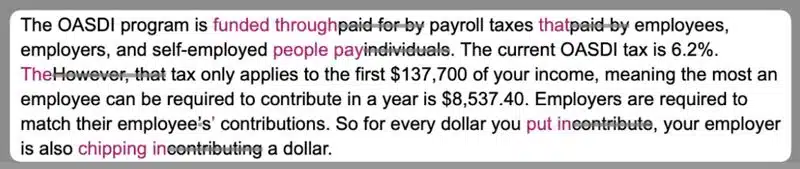

For example, take a look at the following “edits”:

As you can tell, these are done by a good “writer,” perhaps, but as an editor, it’s often missing the point.

The best editors are often akin to a coach. Their job is to sit at the intersection of the brand, the reader and search intent, then make sure to erect “bumpers” on each side to keep writers clear on the primary direction of travel.

- “The best editors maintain a radical focus on the reader. They’ll even break well-established writing rules to serve that focus,” affirms Lindley.

- “Getting into more specific areas of focus, editors should put structure, skimmability and search intent at the center of nearly everything they do.”

- “The other stuff – images, line edits, spelling, grammar, etc. – is important. But you can have all that extra stuff completely perfect and still have a bad article because you’ve neglected structure, skimmability or search intent.”

- “That’s not to say editors shouldn’t care about other concerns. They should, but if I only had 30 minutes to spend editing an article, I wouldn’t change a single word before I addressed those three Ss.”

Lindley is also a proponent of role specialization, where “strategists focus more on keywords, distribution, and the like,” while the writer can “focus on the sentence-level stuff.”

The editor might review all of these details prior to publishing, but none of them outweigh structure, skimmability and search intent.

How do you help enforce (or reinforce) these principles in practice? Especially at scale or higher volumes across a broad team?

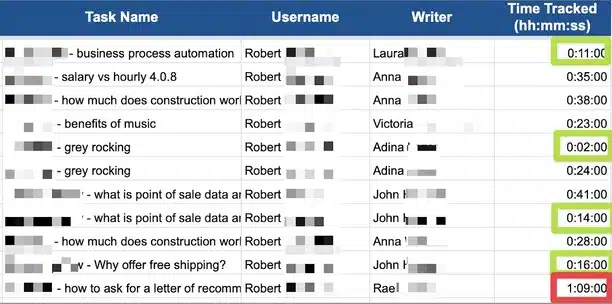

The best way I’ve found is to make editors track time against every article, writer, and content type. Then, set established benchmark thresholds for each.

For example, after publishing thousands of articles each year over the past few years, we’ve noticed that if editors continuously spend over an hour editing certain articles, it actually indicates:

- A process problem (identify underlying gaps in briefs/templates).

- An internal documentation problem (ICP/product positioning communicated + re-trained).

- A role/expectations problem (editors wanna rewrite vs. edit).

- A delegation problem (editors/content managers ‘need to do it themselves’ vs. building a systematic workflow with the first three above).

And often not a “writer” or “editor” problem.

Here’s how to set up this internal feedback loop to make sure everyone is focused on the highest and best use of their respective times (and skills):

- You should have estimated editing time ranges, including caps, to edit each content type, format, or length.

- Add time tracking per article and per writer (even more true if editors are fixed cost / in-house / full-time).

- Use this baseline data to identify trends, patterns and bad habits (rewriting vs. editing).

- Force editors to flag underlying issues or gaps – not just fix surface-level issues – that should have been better spelled out, structured or illustrated for writers in preceding steps.

- Review these issues weekly to create new supporting resources to continually re-train your editorial team.

This feedback loop has two benefits:

- Editors’ editing-per-piece effort will drop like a rock, resulting in a better experience for them.

- It also allows editors to edit more content in the same amount of time, which is a better ROI for you.

The end result is that more editing comments should follow Lindley’s recommended three S approach, providing broad, strategic recommendations like the comment below early on – as opposed to the individual rewording of sentences at the start of this section.

A balanced content strategy delivers evergreen results and boosts revenue

There’s a constant tension when writing for search and readers. Lean too far in either direction and the final outcome can often sacrifice one at the expense of the other.

The trick, as with most things in life, is to lean into the gray area filled with nuance. While also avoiding knee-jerk reactions that try too hard to oversimplify.

If you want readers to consume, engage, save, and share search-driven content, the answer isn’t to start cutting important context like your introductions. Instead, you should be writing introductions that deserve to be read.

Building your publishing process (and editing) around the three S approach are a perfect start to walking this fine line.

Because structure, skimmability, and search intent aren’t just simple, practical guardrails for editorial teams.

But also the foundation behind writing marketing content that also gets evergreen results at the same time.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.